March is a grey month. It spurs the contemplation of life amid the residue of winter’s death.

I walk along the winding path, the old snow sprawled about me in heaps of lassitude. A flock of geese soar through the dull sky, and ahead, two bare trees lean together, their branches tangled like the disheveled hair of two aging women deep in thought.

I reach the book box. Inside I find pop fiction novels, and a social justice bestseller, but there are no works by Fyodor Dostoevsky. I close the book box and continue along the path.

A Substack writer who identifies as

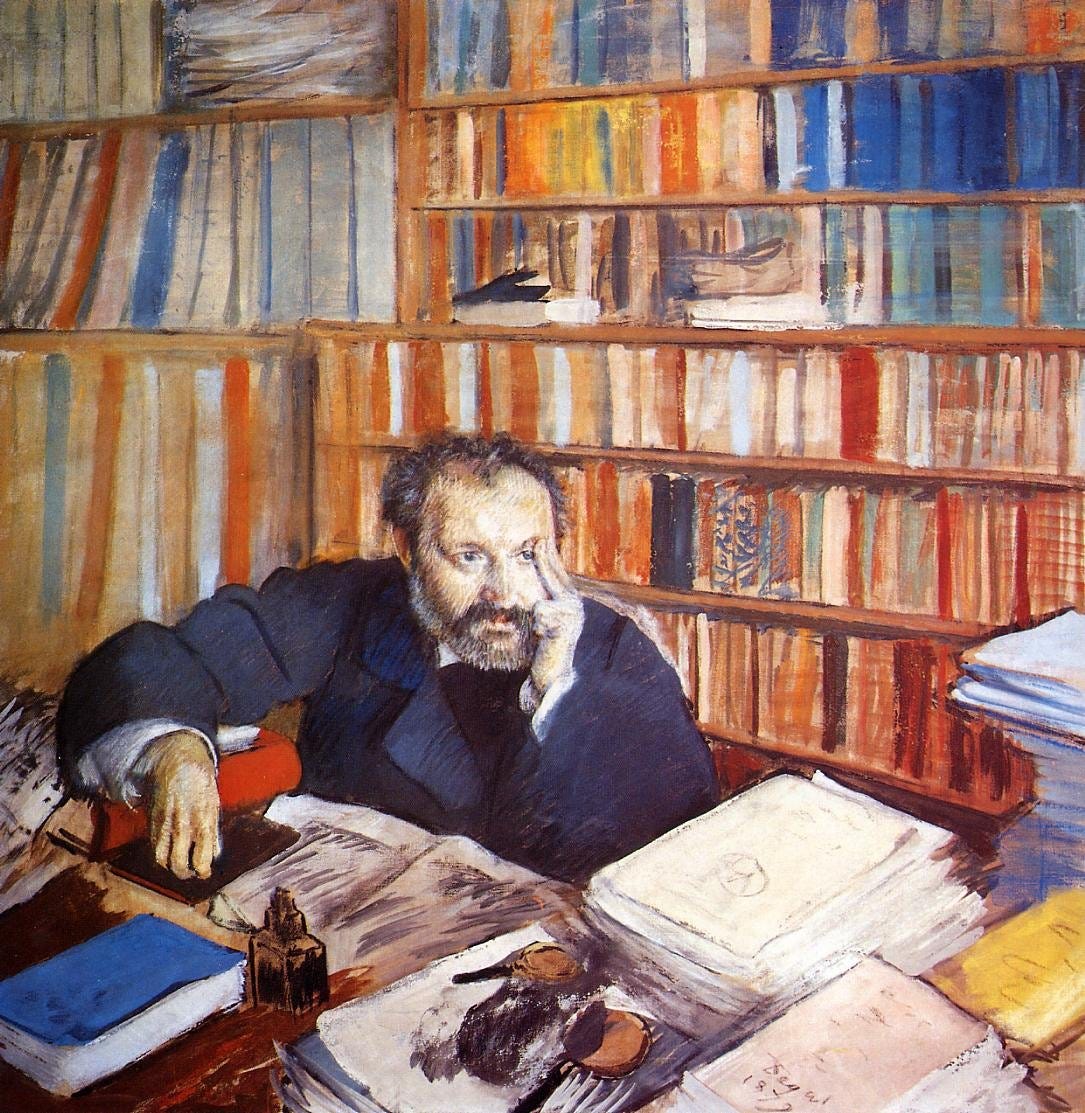

is using artificial intelligence to write his articles in the style of Dostoevsky. One of his most recent posts received over 5000 likes. It’s convincing, and does sound Dostoevsky-ish, or at least like a Russian intellectual from the 1800s, hunched in a room of books with an empty bottle of vodka, and an icon of the Mother of God hanging askew on the wall.And what is AI-Dostoevsky brooding about? Why, the thing we are all brooding about: our addiction to our smartphones.

AI thoughtfully brooding on the dark side of technology is an entertaining irony. No wonder the post went viral. My most-read essay (though not so viral) was on the same topic. There is something admittedly stirring about AI seeming to think deeply about the impact of AI thinking deeply.

As Fyodor explains on his About page:

The AI’s contributions, though generated, are shaped by the essence of Dostoevsky’s narrative techniques, themes, and ideas. Yet, I—the human collaborator—guide and shape these outputs, making them into a coherent dialogue that balances the digital and the profoundly human.

It’s not clear how many of Fyodor’s readers are actually aware of the human-AI collaboration. When my wife

read the piece about smartphone addiction, she thought it was written by a real person, only to feel “creeped out” when she realized the truth. Why? The text had stirred emotion in her. To discover that it was partly (or mostly?) a machine felt violating.Fyodor’s text is well-wrought—I will not say written—yet almost too well, too polished. If AI is already this good, what’s next, a Booker prize? And what might that do to us as readers and writers?

Don’t be a Technovert

Just the other day, I was making notes for a short talk I’ll be giving soon, when I realized I needed a few images for the presentation. The problem was, the images I had in mind didn’t actually exist. For example, I needed a picture of a road sign that read “Don’t be a Technovert”. A technovert—a word I made up—refers to people who spend so much time on technology that they are not intro-verted or extra-verted, but techno-verted: the center of their lives isn’t located somewhere in the real world, but buried somewhere in their devices.

So, I googled the Microsoft Image Generator, and I asked it to create a sign that said “Don’t be a Technovert”.

Yes, I confess: I went to technology to make a picture about a problem caused by technology. Later, I repented of my “digital sin” and asked my younger son to illustrate it for me. Still, I did what I did, and I must be honest, it was entertaining. After typing in the request, I clicked my index finger on my mouse, activating the “generate” button, and then waited while particles swirled dreamily in four windows on the screen. A few seconds later, four different images appeared. Not bad, but not what I wanted.

So I clicked generate again, and four new images appeared. I clicked the mouse button quite a few times, just for the fun of it. The power of AI really is amazing, although I soon realized I was mostly just doing finger exercises with a dumb grin on my face.

And the more powerful AI becomes, the more our “collaboration” with it becomes just that, a finger exercise, a physical digit pressing a digital button. Generate. Generate. Generate.

Wait—I just heard something.

There it is again. A low-pitched tone. I pause from writing this article, and look around the room. I am confused. Where is that deep tone coming from?

I rise from my chair and peer through the window. There is a man outside, wearing a hard hat and orange construction vest, and on the road beside him is a device I have never seen before: a rectangular box on a metal frame.

There it goes again, that tone. It ascends in groups of three or four notes, then stops, then repeats itself. Curious, I hurry back to my computer. An internet search reveals the device to be a “SL-RAT transmitter”. Apparently it uses acoustic signals to determine if there is a clog in the drainpipes under the road.

Notice the direction of the technology: the SL-RAT transmitter draws attention to itself through a series of tones, for the purpose of directing our attention into the real world—the sewer pipes. It is not a technoverting device. It does not draw our attention to itself to keep our attention there. It points us to the world of asphalt, iron, meltwater, debris. It tells us whether somebody needs to go down there and clear the drainpipes.

It’s also a metaphor for why it’s so hard to resist AI. We need to do our own creative work, but it means entering the drainpipes of the psyche and dealing with the effort, the angst, the debris of writer’s block. This is what writers do. This is what the real Dostoevsky did. We go inward, into the complicated places, to come back out again clutching a sheaf of papers, and to declare: This came from the depths of my spirit!

From my spirit. The heart of a human being.

When we read a novel, we often find ourselves empathizing with the characters and their world, and implicitly with the author of the book. It’s a profound thing, yet it’s no illusion. The author’s writing sends an emotional vibration through the words that reaches inside us, stirring our own feelings and imagination.

AI does not have emotions. It will, of course, get better at persuading us that it does, but it will never be anything more than a machine posing as a human, using all its powers to charm us into believing there’s a real mind and heart behind the screen.

When actual humans try to charm us into believing their deceptions, we call them sociopaths. Oddly, when machines do it, we call it amazing and groundbreaking.

Still, I’ve pressed the generate button. I know the dopamine delight of waiting to see what happens, and the urge to press generate again. And some people, like Substack Fyodor, are experimenters by nature. We should not judge how people play in their personal AI sandboxes; yet we can, in a cause-and-effect sort of way, discern the potential implications outside of those sandboxes.

For my part, I sense that the further AI progresses as a creative technology, the more we’ll become convinced that it’s outputs are authentic in the human sense—whereas it’s still just a plagiarism machine on an industrial scale.

One might argue that AI-Dostoevsky’s advice about smartphones isn’t technoverting, if the advice moves us to reduce our phone use and engage in the real world. Or that an AI-Emily Dickinson wouldn’t be so bad either, if her poems helped us to appreciate the beauty in life.

Maybe—if we actually did what they suggested. But will we really stop pressing that button long enough to leave the screen? Generate. Generate. Generate. The potency of AI’s writing, like digital vodka, might instead only deepen our addiction to its spectacle.

As for creators, AI’s progress may invite us to drift further away from actual literary creation, and to become mostly finger-pressers who work with vibes rather than words. Finger-painters of impulse, whose language skills dry up.

In the end, will anyone care who the real Dostoevsky is?

The writer sighs and rises from his desk, and gazes out at the grey day. A hackberry tree stands in the yard, stiff as an old broom, yet in the tangle of the branches is a flash of living yellow. A goldfinch.

A skitter of hope, he thinks.

Live Meeting

Come and join me and Peter Limberg for a deep dive into the “3Rs of Unmachining —Recognize, Remove, Return — and confront The Pull, the force that keeps us trapped in compulsive digital distraction” on March 22nd at 12 PM EST followed by a discussion period. See here for details and registration.

Offers and announcements

My novel Exogenesis is entirely human written. Find it at the publisher, Ignatius Press, or at The Unconformed Bookshop and various other booksellers. Reviews here.

Come and join me, Ruth Gaskovski, and Dixie Dillon Lane on the Camino Pilgrimage in Spain from June 14-24. Space is limited, so reserve your spot now. You can read all about it here or download the brochure here (note: if the registration site shows SOLD OUT, contact us directly at schooloftheunconformed@proton.me, as we are still trying to make some spaces available). We would love for you to join us in visiting historic sites, sharing meals, building relationships, all while hiking through a naturally and spiritually inspiring landscape.

Excellent Peco

BTW many don't know. AI is not a post modern invention. I worked on it more than twenty years ago...

I found myself thinking about Aquinas after finishing this piece. There’s something about the way AI and its ease of use captures our attention and enraptures our desire. Even for the “good things,” but it also facilitates a habitual disposition toward those things that is in some sense corrupting.

I think there is something difficult to think about with that that your piece raises. Maybe: that despite AI's ability to facilitate engagement with virtuous things, it somehow is false in the way by which we are disposed toward such things? This is an incomplete thought, but now I'm encouraged to close my computer and think about it, or maybe re-read an article of the Summa. I fear this may be a bigger question than I could even begin to contemplate here. Thank you for the thought! Big fan.