Horses in the Heart: Passions, Distortions, and Ultimate Hope

Stories that help us leap over oncoming trains

Alex Colville’s Horse and Train was painted in 1954. It naturally pulls for interpretation. Decades later, when copies of the image were viewed by artists living in Communist China, they thought: We are the horse and China is the train. In our time, we might think, “We are the horse and technology is the train”. We are galloping toward calamity. But there is a more nuanced interpretation, not quite as pessimistic: the horse represents our passions—our impulses, desires, emotions, instincts—and technology is the train track, which can potentially channel those passions in a dangerous direction.

How do we manage our passions, which are sometimes energizing and positive, and sometimes unpredictable and destructive? It’s an ancient question. Plato used the metaphor of two horses, the one good and noble, and the other unruly and rebellious, steered by a chariot driver who is the rational human soul struggling to manage the opposing natures within us.

Our society often esteems intelligence, yet arguably our most serious failings are not failures of intelligence, but failures of passion. Failures to keep a good rein on the horses in our hearts.

The idea of keeping “a good rein” suggests using effort to control our passions. Through force of will, we might suppress an unhealthy temptation, or distract ourselves from unwanted feelings. But the use of effort or willpower is an energy-consuming way of manage our passions, and often it fails. A more elegant and potent way is to have a story that tells us why we need to manage them.

Often such stories are given to us through our culture or upbringing. These stories aren’t necessarily complex; sometimes they’re simple heartfelt beliefs, or maybe a value embodied in the life of a person we admire. Either way, the unique power of stories is they can steer our horses not by pulling on the reins—not by effort or willpower—but rather as if someone had whispered in the horse’s ear and subdued its imagination.

Over a century ago G.K. Chesterton wrote that “the most practical and important thing about a man is still his view of the universe”. The only difference today is how easy it is for us to share our views of the universe through digital platforms. The internet is a place where people are incessantly whispering in the ears of each other’s horses, trying to capture each other’s passions and to send them galloping down train tracks.

The power of distorted cognitions

is the co-author of The Coddling of the American Mind with . Lukianoff had worked defending free speech on college campuses since 2001, but by late 2013 he noticed that students were suddenly becoming much more willing to ban speakers and punish people for ordinary speech. Lukianoff, who has a past history of depression, had also been treated through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and noticed an odd parallel between CBT and the thinking styles of intolerant students.CBT is premised on the idea that many mental health problems like depression are due to distorted beliefs about the world, like “catastrophizing” (always assuming worst case-scenarios), “emotional reasoning” (interpreting reality through our feelings), and “all-or-none” thinking (interpreting situations in black and white terms, without nuance). CBT works by helping clients to recognize their distorted cognitions and to replace them with a more realistic picture of the world. In essence, CBT changes how we feel by changing the stories we tell about ourselves and the world around us.

Going back to Lukianoff, what he noticed after 2013 is that students’ increasing intolerance seemed to be driven by distorted cognitions. As Haidt describes it:

What Greg saw in 2013 were students justifying the suppression of speech and the punishment of dissent using the exact distortions that Greg had learned to free himself from. Students were saying that an unorthodox speaker on campus would cause severe harm to vulnerable students (catastrophizing); they were using their emotions as proof that a text should be removed from a syllabus (emotional reasoning). Greg hypothesized that if colleges supported the use of these cognitive distortions, rather than teaching students skills of critical thinking (which is basically what CBT is), then this could cause students to become depressed. Greg feared that colleges were performing reverse CBT.

The recently released documentary for The Coddling of the American Mind, directed by

, goes deeper into how “reverse CBT” took hold on many campuses and elsewhere in society, and—importantly—how it was associated with a steep rise in social media use and safety-focused values starting around the early 2010s.Luxury beliefs are another example of distorted cognitions, although they aren’t derived from CBT.

, author of Troubled and , coined the term “luxury beliefs” to describe beliefs that some affluent people may broadcast to the rest of society, as it doesn’t cost them anything and puts them in a good light, although it may inflict a cost on less fortunate people.For instance, Henderson points out that affluent people are the most likely to claim that their success is a matter of luck or connections (although they may privately tell their own children to work hard). This luxury belief doesn’t alter the affluence of the affluent—they’re still rich and powerful. But the same belief risks undermining the self-efficacy of less affluent people, as it might make them less inclined to believe in the importance of hard work.

Luxury beliefs, like reverse CBT, are distorted cognitions—essentially, they are faulty stories about the world, and can mislead where we direct our energies.

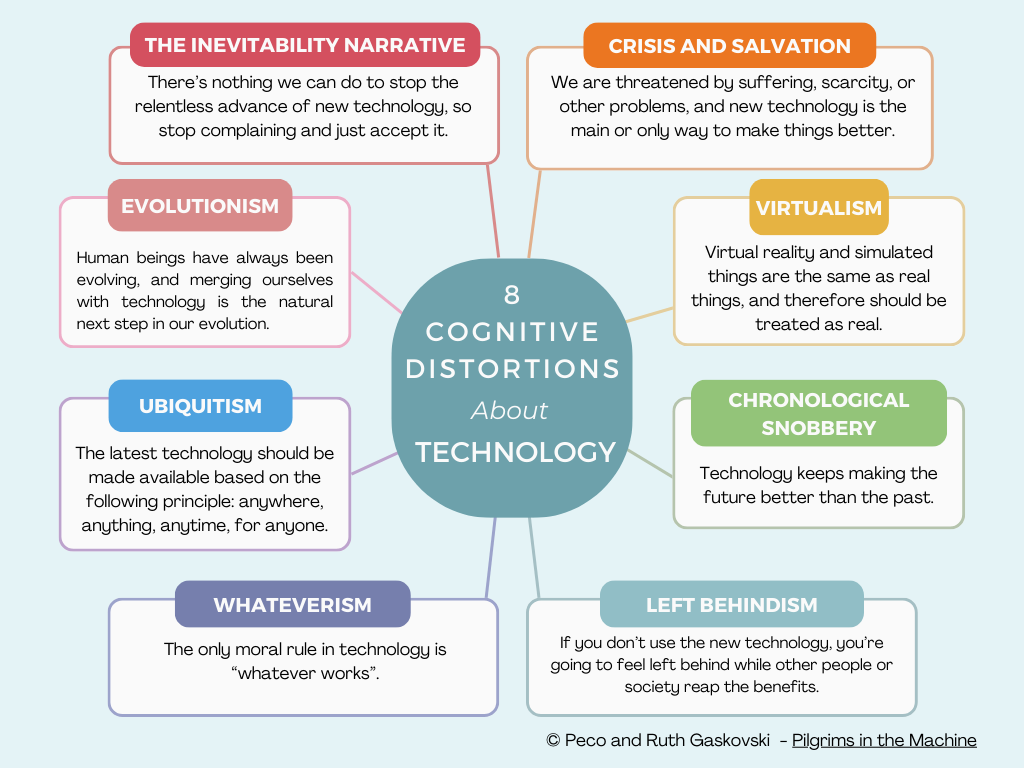

Distorted cognitions can be found throughout society, and across the entire political spectrum, both left and right. Some of these cognitions are also about technology itself. They are often given to us through tech marketing, or commentary by cheerleaders of new technology. Eight common examples you may recognize include:

The Inevitability Narrative: There’s nothing we can do to stop the relentless advance of new technology, so stop complaining and just accept it.

Crisis and Salvation: We are threatened by suffering, scarcity, or other problems, and new technology is the main or only way to make things better.

Virtualism: Virtual reality and simulated things are the same as real things, and therefore should be treated as real.

Chronological snobbery: Technology keeps making the future better than the past.

Left Behindism: If you don’t use the new technology, you’re going to feel left behind while other people or society reap the benefits.

Whateverism: The only moral rule in technology is “whatever works”.

Ubiquitism: The latest technology should be made available based on the following principle: anywhere, anything, anytime, for anyone.

Evolutionism: Human beings have always been evolving, and merging ourselves with technology is the natural next step in our evolution.

How do we correct distorted cognitions about society or technology? Sometimes we can do it through critical thinking, logic, or even common sense. A lot of the time, though, our instinct is to go online to search for answers. But that doesn’t always help.

The world’s information flows through the internet, but so does the world’s passion. We may go online to find clarity on a subject, only to find the subject distorted by passion-focused reasoning. We can end up being persuaded not so much through information or facts, but through the emotions—like outrage, fear, guilt, desire, pleasure—that are associated with the information or facts.

How do we resist passion-focused reasoning? Is it possible to reverse the “reverse CBT” that the internet and online realities can inflict on us?

Reversing reverse CBT

In actual CBT therapy, distorted beliefs are corrected by finding objective evidence that contradicts those beliefs based on observations of the real world. For instance, we might believe we’re failures, until we look more closely at our lives, and realize we have many areas of success. Or we might think we can’t cope with our anxiety, until we confront the anxious situation and discover it isn’t as bad as we imagined. It’s only by connecting to objective reference points outside the self that we can correct the distorted perceptions within the self. Attempting to correct our distorted cognitions without an objective reference point leaves us at the mercy of being trapped inside ourselves, within our own cognitions and feelings, and potentially in an endless loop of distortions.

A few summers ago, we were in Switzerland and paid a visit to the country’s oldest hall of mirrors, the “Hall of Mirrors Alhambra” built in 1896. If you’ve never been to a hall of mirrors, it’s a disorienting experience. All the passageways are mirrors, so you’re surrounded by reflections of reflections. You can never be sure where one passage ends and where another begins, whether the person behind you is really behind you or in front, whether a turn around a corner is a real turn or a dead end. During that visit, we walked through the hall several times, and I (Peco) was struck that, while I had memorized some of the actual (versus illusory) turns in the passageways, I ended up doubting myself and kept bumping into glass, so powerful was the illusion.

Much of the internet itself is a hall of mirrors: comments about comments, ideas about ideas, reflections of reflections. The internet is also a global bloviating machine, and generative AI will amplify the bloviating, as the creation of more content based on existing content will add endless new mirrors and distortions to the hall. Any attempt to correct our distorted cognitions about the world based on things we see or read on the internet is at high risk of deepening that distortion, as we can never be sure which ideas are true and which are not.

If we want to reverse the reverse CBT, the only way is to get out of the hall of mirrors. In our last essay, we introduced the songbird compass as a method for exploring whether a technology is “good” or “bad” based on whether it points us toward or away from reality. But reducing our tech use through this method, or any method for that matter, can still be difficult, as technology itself can be habit-forming, addictive, or just irresistibly “fun”. Passion keeps us going back to it.

Our compass needs another component to work properly. Something more powerful than common sense or logic.

More Mennonite than Luddite

In 1995, Kirkpatrick Sale used a sledgehammer to smash an IBM personal computer at an event in New York City. Sale had authored a book on the Luddites, the English textile workers from the 19th century who are often remembered for destroying the new industrial machinery that threatened their livelihoods. Sale considered himself a neo-Luddite, and smashing that computer was the ultimate gesture of rejecting technology.

Sales wasn’t the last of his kind. More recently, neo-Luddites in San Francisco discovered that a self-driving car can be immobilized by placing traffic cones (or any similar object) on the hood, as it blocks the vehicle’s sensors for seeing the road. The tactic allowed the Luddites to stall dozens of autonomous vehicles all over the city—an act described as “vandalism” by the companies that operated the vehicles.

Still, self-driving cars will probably proliferate, just as computers and textile machines have proliferated. The classic Luddite approach—passionate acts of resistance against technology—might be emotionally rewarding in the short run, and stimulate important conversation, but they probably won’t do for the long run. Much as we dislike something, we cannot build a society by acting through a negative passion. We must be constructively for something; we must be for it so much that whatever we are against is more a byproduct of what we are for, rather than a primary passion in itself.

We were visiting friends in the country when I snapped the photo above. Mennonite horses and buggies aren’t an unusual sight in these parts, and I had actually been intending to take a picture of the distant tree in the background, when the buggy came rolling along. For weeks I could not get the image out of my mind: the horse with its head raised and mane fluttering, like a silhouette of nobility, and behind it a black box on wheels and a man with an Alfred Hitchcock profile at the reins. The wild and the controlled. The graceful and the prosaic.

The Old Order Mennonites, and the Amish like them, have endured for hundreds of years, and the limited use of technology in their daily lives might make them seem like Luddites of a kind. But the story guiding their identity and their passions is not focused on opposing technology, but on their religious faith, families, communities, and farm-life.

Most of us wouldn’t want to live like the Mennonites or Amish, but as we struggle against the distorted stories that technology tells us about life or about technology itself, we too need a story about what we are for, not against; a story about why embodied humans matter, why the natural world matters, why love and sacrifice matters, why the work of our hands matters.

And this story can’t just be any story, nor even simply a great story. Ruth and I once had a friend who read the classic novel The Robe, about a Roman centurion who wins Christ’s robe as a gambling prize after the Crucifixion. Our friend was so inspired by the novel that he became a Christian. But he was a voluminous reader, so he was eventually inspired by other novels and dropped the Christian story in exchange for other stories that happened to seize his imagination more intensely. Even books can be halls of mirrors, it seems.

Anchoring a story primarily within ourselves or within a hall of mirrors—whether internet, books, words, or any other medium designed to represent reality—risks being distorted by our own passions or by somebody else’s. The anchor for the Amish and Mennonites is a God who points them back to their marriages, children, family, work, and land. All of these things are all objectively real reference points outside the self. They have the power to correct distorted cognitions about reality, as they themselves are real, not merely representations of the real.

A Well-Grounded Hope

We all need a story about life that shapes and guides our passions toward the real. This can be difficult in a society where, increasingly, the only reliable story we tell about our passions is that, other than indulging our passions, we must not interfere with anybody’s wish to indulge them. Passionate non-interference of the passions is the cardinal virtue of a post-modern world.

That virtue is misguided, yet it’s rooted in something true. We are creatures of implacable feeling. It can be difficult to manage our wilder energies. The horses of our nature can be overwhelming, and sometimes we think, “Just let them run free, they’ll be okay”.

That might work if we were only horses, or only wolves, birds, or fish, purely natural. But human beings are not like other animals. We are not purely natural, but uber-natural, beyond natural, half horse and half wagon driver. We can’t entirely set those horses free any more than a wagon driver can release the reins and expect to stay on the path. But we can’t control our passions through forceful pulling on the reins, either. We need a story that guides us away from passion-focused reasoning and cognitive distortion, and toward trustworthy realities outside of ourselves. We can’t escape this need; we are creatures of cognition as much as passion.

More than our intelligence or our wealth, how we steer our passions will determine the health of our families, the stability of our minds, the fullness of our creative powers. To a great degree it will also determine how we respond when we see the train barreling down the tracks toward us.

For the Chinese artists, the train was their Communist government; for us it might be the thunderous charge of technology. But it could also be some other calamitous threat that makes us anxious, discouraged, and hopeless.

World War II began on September 1, 1939, and a few weeks later, on October 22, C.S. Lewis delivered a lecture at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, in Oxford, titled Learning in War-Time. What, Lewis asked, is the point of learning anything when you’re facing a world war? Why bother studying poetry, or chemistry? How can we be so frivolous and selfish as to think of anything but the war?

Yet Lewis reminds us that

The war creates no absolutely new situation: it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it. Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice…If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun. We are mistaken when we compare war with ‘normal life’. Life has never been normal.

In our own time, the train barreling toward us might fill us with doom, yet the situation isn’t unique. There have been dooms before; there will be dooms to come. This is historically normative. We must keep living, whether scholar or soldier, mother or mechanic, whatever our purpose. But we don’t have to be grim. Lewis suggests we can defend ourselves against fear, frustration, and other destructive passions by grounding ourselves in an ultimate hope, which for him, as a Christian, was a life humbly offered to God.

While not everyone will share Lewis’s worldview, we can all ask: What is the guiding story of our lives? What cognitions, ideas, and understandings hold us securely to real people and real things? What story helps us understand how to manage our wilder passions, while releasing the possibilities of our nobler energies?

And if our story is grounded in a trustworthy, ultimate hope, it won’t matter that a train is thundering toward us. We’ll have the legs to leap over it, without growing weary or faint.

We would love to hear from you! Please share your thoughts, reflections, and questions in the comments below.

Until next time,

Peco and Ruth

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), and if you would like to support our work of putting together a book on “The Making of UnMachine Minds”, please consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share.

Links

You can now stream The Coddling of the American Mind exclusively on Substack.

and his team are also taking the film on tour around university campuses. For details see this post.

New in the Unconformed Bookshop:

- (set to release on March 26th)

Troubled by

You can find an updated reading list (and pdf download) of “Unmachined Words” in the post below. Be sure to view the comment section for additional recommendations by readers.

Thank you for this promising post! I will come back to read more carefully and comment more fully later, but I want to pop in right now after skimming and mention that my "dumbphone" is produced by a Mennonite company, which sure does feel right! https://sunbeamwireless.com/the-story-behind-sunbeam-phones/

Grateful to you for this exquisite post! Knowing that writers can still be found who help us all with our "mirrors" is why I subscribe to Substack. This is an excellent piece and should be widely read. Thank you with the greatest appreciation!