Pandora’s Devices: Managing the Miseries of the Machine

Marriage is weird, Lincoln was wise, and six words that can transform a relationship

We had a bad feeling about our new neighbor, Jeff, when we saw the 12-inch cannabis bong on the table of his back patio, standing proudly. A “bong”, if you’ve never heard the word, is a glass water pipe used for smoking.

Jeff smoked pot before sunrise. He smoked multiple times through the morning and afternoon and evening, and into the late hours, and sometimes in the middle of the night. We knew this not only by the skunky smell that wafted into our yard, but because Jeff had a deep, hoarse, wet cough. When Jeff started coughing it was like Godzilla hacking up pieces of downtown Tokyo.

We could hear it anywhere in our house, even with the windows closed. We couldn’t enjoy our meals in the backyard, or any time in the backyard at all, as Jeff would invariably end up puffing up a storm. What could we do? We certainly couldn’t complain he was doing anything wrong, since recreational cannabis use is legal here (not just decriminalized). We felt powerless. Irritable. Outraged. But we knew we had to do something.

Our overriding instinct was to rail at our Gen Z cannabis-hooked neighbor over the wooden fence that separated our yards. “Don’t you have any idea how disruptive your pot-smoking is? Don’t you notice we have children? Don’t you have any awareness of the world around you? Don’t you, don’t you, don’t you…?”

Then we made a fateful decision that would change our relationship with Jeff forever. We collected some eggs that our chickens had just laid, and called out to Jeff over the fence: “Hey Jeff, we’ve got something for you.” No, we didn’t throw the eggs at him. They were a gift.

The purpose of the gift was not to placate Jeff, since he wasn’t the angry one. He was rather cheerful actually. The purpose of the gift—though we didn’t quite realize it at the time—was to create a shift in our own perception of Jeff. Through an act of benevolence, we instantly replaced the idea of punishing Jeff with being generous to Jeff. We changed as a result.

Suddenly our outrage vanished. Our irritation didn’t go away, but we could laugh about it sometimes. We even felt comfortable enough to ask Jeff if he might refrain from smoking whenever we happened to be outside having a meal. And Jeff was perfectly agreeable with that.

We make our friends; we make our enemies; but God makes our next door neighbour.

- G. K. Chesterton

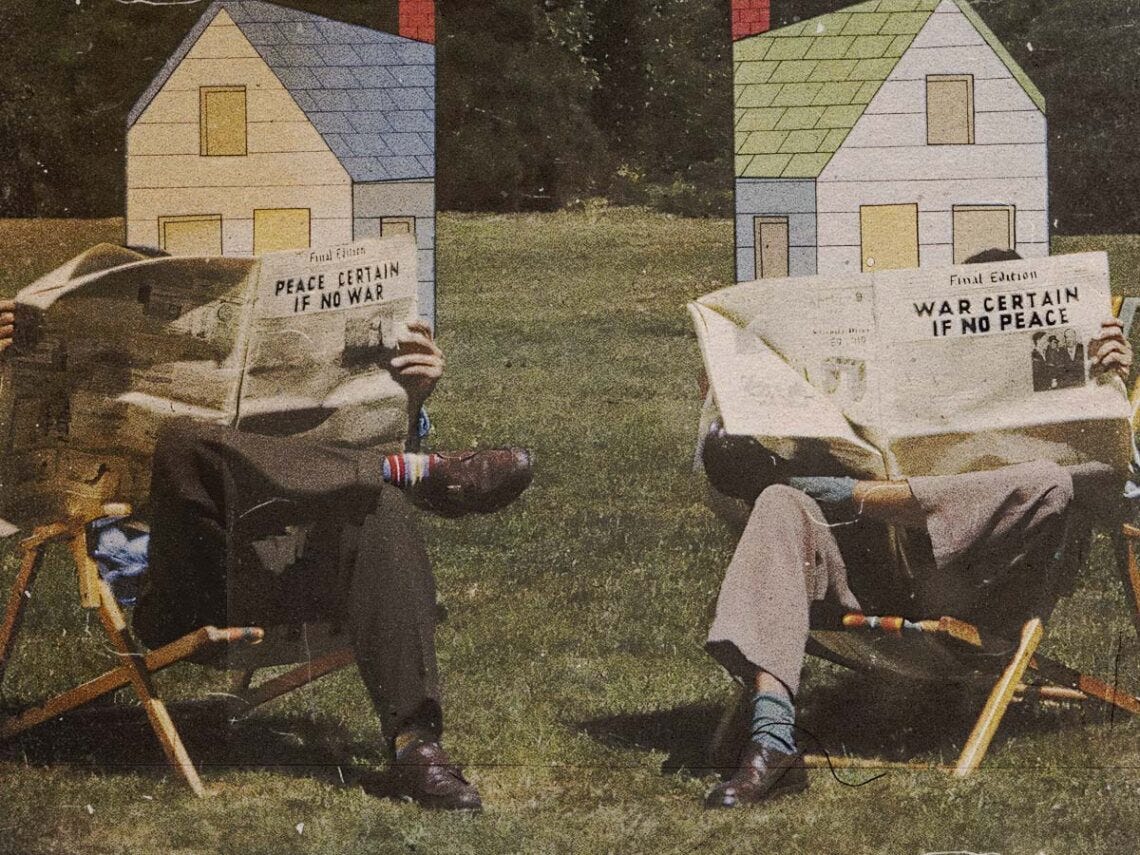

The ancient Greeks gave us the myth of Pandora, who received a cursed wedding present in the form of a box that, when she opened it, unleashed misery and evil on the world. The situation with Jeff presented us with a kind of Pandora’s Box. We had to decide whether to open the box—to speak up about his behavior and risk offending him, which might unleash conflict and make the situation worse—versus attempting some other action.

Not everything that spills out of Pandora’s Box causes outrage. Sometimes it unleashes milder reactions. In some cases we might even want to open our Pandora’s Box, so that others can see who we really are, even if they don’t like it.

We recently attended a wedding. It was a simple ceremony, bracingly traditional. The procession was led by a young girl holding a six-foot cross. We sang O Love, How Deep, whose text goes back to the 15th century, attributed to Thomas à Kempis who wrote The Imitation of Christ. The vows were traditional too, comparing the union of husband and wife to the union of Christ and the Church.

When you think about it, marriage is a unique thing. Even a weird thing. There is no other relationship in the world where two complete strangers come together, and each decides that the other person will be at the center of their own life, and that they will both keep this center permanently, to the exclusion of all other such relationships, until death.

That makes no sense in a world where almost everything is refundable, or redefinable.

points out that having an affair is now considered by some an act of “self-care”. No wonder marriage can make some people cringe.There were a lot of Gen Z’s at that wedding, and not all of them were Christians. What did they think about all the monogamy and God talk? What would they make of this bride and groom, who were serious enough about their religious beliefs to have abstained from living together—and probably from sex—until marriage?

Maybe some of those Zoomers squirmed or snickered through the ceremony. People have ways of dealing with the little Pandora’s Boxes of life, ways that don’t cause much harm. But there are also bigger boxes, enormous ones that provoke hostility and strife—and yet they often fit in the palms of our hands.

Pandora’s Devices

There is a playground near our home where parents gather during warm evenings to chat while their kids play. The conversation is usually easygoing, although sometimes a Contentious Subject comes up—politics, for instance.

Standing there in a circle of perhaps three or four, we are face to face. We see each other’s eyes. We see each other’s body language and hear the tones in each other’s voices. We can recognize when things are getting tense or awkward and can shift the conversation, if need be. We are motivated to keep the peace.

We are neighbors, after all. We have a stake in each other’s well-being. Even if we don’t agree on certain Contentious Subjects, even we if know that somebody carries a Pandora’s Box inside them whose contents might spark outrage, that’s relatively less important than getting along. We know how to keep our boxes closed, when there’s no good in opening them.

This has always been a baseline challenge for humanity. All through history, people have walked around with a Pandora’s Box that could unleash chaos on their relationships, or at least prickles of annoyance, if they weren’t careful.

Abraham Lincoln was profoundly disappointed when General Meade didn’t act quickly enough to stop the Confederate army from escaping after its defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg. Lincoln even wrote a letter to Meade, telling him, “Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.” But Lincoln never sent the letter. Abraham Lincoln had a practice of writing angry letters he never sent—“hot letters”—as a way of cooling off his emotions and keeping his Pandora’s Box safely closed.

If Lincoln were alive today he’d probably resist getting a Twitter account. Digital boxes are harder to keep shut. Complex and painful human experiences that happen far away from us—in other communities or cities, or on the other side of the planet—can find their way into our own Pandora’s Box. It can even happen by accident. We thought we were looking up the weather report, and instead found ourselves in a war zone, with a reporter, or politician, or victim, explaining what it all means. We absorb other people’s rage or misery and make it our own. In our neighborhoods, we would never dream of ripping the lid off our Pandora’s Box and spilling chaos into another person’s face. On social media people digitally spit at each other with abandon.

Our devices and the excessive time we spend on them are also changing our real relationships.

, a Generation Z (Zoomer), writes,The day-to-day life of a typical teen or tween today would be unrecognizable to someone who came of age before the smartphone arrived. Zoomers are spending an average of [up to] 9 hours daily in this screen-time doom loop…Uncomfortable silence could be time to ponder why they’re so miserable in the first place. Drowning it out with algorithmic white noise is far easier. Is it any wonder that kids today are strangers to the people who raised them?

To this we might add: Is it any wonder that kids today—and increasingly adults—are strangers to each other?

Before digital technology a lot of the 9 hours that we now spend on screens were spent with actual people, doing real things in real places. We built up a history with our neighbors and community. We were not strangers. We might not know each other intimately, but our common history gave us a shared identity, and a buffer of mutual sympathy that protected us from the emotional shock of any Pandora’s Boxes that might open up between us.

The Wisdom of Athens and Jerusalem

In a recent opinion piece in the New York Times, David Brooks talks about the brutal realities we’re facing today:

Scenes of mass savagery pervade the media. Americans have become vicious toward one another amid our disagreements. Everywhere I go, people are coping with an avalanche of negative emotions: shock, pain, contempt, anger, anxiety, fear.

The first thing to say is that we in America are the lucky ones. We’re not crouching in a cellar waiting for the next bomb to drop. We’re not currently the targets of terrorists who massacre families in their homes. We should still start every day with gratitude for the blessings we enjoy.

But we’re faced with a subtler set of challenges. How do you stay mentally healthy and spiritually whole in brutalizing times? How do you prevent yourself from becoming embittered, hate-filled, calloused over, suspicious and desensitized?

Brooks’s answer rests in two sources of ancient wisdom, the one from the Athenian Greeks, who cultivated a tragic sensibility toward life, the other from the ancient Abrahamic religions, which encouraged “leading with love” in harsh times.

The first view gives us realism and humility, by reminding us that social strife and even barbarism are historically normative (we’re just lucky, if we haven’t experienced it). The second view impels us toward what is highest in human beings—a compassionate view of others.

There’s a core of solid wisdom here, although applying the wisdom now may be more difficult than in the past. Although Brooks rightly lauds the resilience of the ancient Athenians, Socrates wasn’t hooked on TikTok and Pericles wasn’t playing Fortnite. Athenians were part of a city-state with a shared identity over a long history. They definitely weren’t strangers to each other.

Resilience comes more easily in close communities, where the community can soften the sting of personal suffering. We tend to forget that in our more individualistic age. Resilience isn’t just an individual trait or attitude, but the emergent property of a wider social fabric in which real people take care of other real people. Ironically, individuals who exist within this kind of fabric and who have never heard the word “resilience” are probably more resilient in the face of tragedy than isolated people who read inspiring essays about resilience on the internet.

This brings us to Brooks’s other suggestion. He observes that when times are harsh, people dehumanize each other, and the way to counter this is with love:

What sunlight is to the vampire, recognition is to those who feel dehumanized. We fight back by opening our hearts and casting a just and loving attention on others, by being curious about strangers, being a little vulnerable with them in the hopes that they might be vulnerable, too. This is the kind of social repair that can happen in our daily encounters, in the way we show up for others.

Being able to give people our loving “attention” assumes that we can pay attention long enough to do that. Our devices pose another challenge here, by tethering our attention to our screens, and distracting our ability to learn to focus on real human beings with skill and nuance.

Our devices might be doing something else to us too. A lot of what emanates from our screens, when it isn’t vitriolic, is powerfully affirming. We know we are right and worthy, because Big Tech’s algorithms ensure that our button clicks lead to another release of dopamine, the feel-good brain chemical. We get a sort of “loving attention” from our devices, yet simplified and sycophantic. You’re wonderful. You’re a winner. You deserve so much. Is it possible this faux compassion is already influencing how we show care and concern for real people in our lives?

Brooks suggests most people “are peace- and love-seeking creatures”. Probably they are. Yet without truth, our love and peace-seeking will be skewed. And it’s not simply that we don’t always tell people the truth. It’s that people are susceptible to believing things that aren’t true. In other words, the same species that is love-seeking is intrinsically gullible, and these two realities don’t always square. People who think they’re wonderful when they’re not, are just annoying, but people who believe wrong ideas can be outright destructive.

That doesn’t negate Brooks’s call toward the practice of loving attention but adds a finer point to it. If we are compassionate without truth, we can end up doing very much what social media does to us: show people what they want, but not what they need.

People often disagree on truth, of course, but that doesn’t mean it’s entirely elusive. We can begin with a willingness to be committedly honest with ourselves and perhaps, gently, with those closest to us. That alone can be transformative.

Sometimes the most powerful words in a relationship are not “I love you”. They are “I was wrong, you were right”. They are more powerful not because they are more true, but because they are more rare.

Sometimes, the only way to close Pandora’s Box is for someone to confess that they were the misery that spilled out of it.

3 Quick Bits of Unmachine News

The Polar Generation

Many thanks to

for bringing this piece to our attention: Writing at First Things, Michael Toscano explores how we might rescue the new generation—“the Polars”, circa 2013-2029—from the distorting impacts of technology. His article comes from a Catholic perspective yet reflects a broader growing awareness of the need for moral and political action against the reckless unleashing of new tech on society:Just like the impunity we granted Silicon Valley to rewire adolescents through social media, the next phase, which seeks to penetrate even further into human consciousness, is a choice masquerading as a necessity. We can and must unmask and unchoose it. But how? There is only one way, and it is entirely unpalatable for those raised to believe that the essence of liberty is the freedom to consume. That way, I am afraid, is politics.

Exquisite Loneliness

has just reviewed David Brooks’s How to Know a Person, together with Richard Deming’s This Exquisite Loneliness. The latter explores how overcoming isolation is the essence of what holds humanity together. In the words of Rod Serling of Twilight Zone fame:Human beings must involve themselves in the anguish of other human beings. This, I submit to you, is not a political thesis at all. It is simply an expression of what I would hope might be ultimately a simple humanity for humanity’s sake.

Unmachining the mind

Readers may have noticed that

(my wife) and I have been collaborating on our posts lately. We are thinking of putting together a book on unmachining that will combine our work on and into a practical handbook for individuals and families looking for anchors of hope in a time of upheaval. If you want to get an idea of our background and our early formative thoughts on “unmachining”, you might want to read:The Making of UnMachine Minds

Fatherhood is a form of insanity, a state in which love and worry become forever entangled. I discovered this insanity one winter night, a few weeks after the birth of my daughter. A blizzard was raging over the town where we lived, and I woke suddenly with a panicked thought:

We would love to hear from you! Please share your thoughts, reflections, and questions in the comments below.

Until next time,

Peco and Ruth

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), and if you would like to support our work of putting together a book on “The Making of UnMachine Minds”, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share.

This quote is confusing me:

"What sunlight is to the vampire, recognition is to those who feel dehumanized."

Vampires hate sunlight because it destroys them. It seems like he is saying that recognition and attention can help those who feel dehumanized to reclaim their humanity. So recognition is like the opposite of sunlight to a vampire. Not really that important, but this was bothering me.

I have found your work & your wife's work very compelling, and it remains high-priority reading for me as I consider my relationship to my devices and technology.

What I notice, though, is a pretty consistent theme that centers people who are married and have children. I wonder if there is any word of hope or counsel in there for those of us who are single and live on our own. Obviously, since I'm reading this kind of stuff, the single-living-alone life is not what I hope for in the long term; I very much desire to meet someone and get married. But I wonder about what to do in the meantime. It doesn't help that my primary options for dating are via apps; and with so many of my friends now married, many with kids, they are naturally now turned inwards toward their own family life and less to friends like myself. I can't help feeling sort of superfluous, or optional, standing on the outside looking in. It becomes awkward to "insinuate" myself into someone else's domestic life for the sake of keeping friendships alive and preserving my own sanity. I'm plenty active in my church and various music groups, so I have lots to do, but there's just something missing for me as a single person. I'd love to know what you think.