Resisting an Attention Deficit Empire

Soft fascination, emotional chaos, and telling the right story about our attention

Not long ago, a friend of mine confided that he had just been diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed Ritalin. Having known him for years, I never suspected he had an attention problem. He seemed a bit distractible at times, and was a heavy coffee drinker, although I could say as much for myself as well.

My friend is also a father and husband, and a successful business professional—so whatever his attention issues before he started on Ritalin, they weren’t bad enough to stop him from achieving more than most people.

Does my friend actually have ADHD? Should he be taking a stimulant medication? Or is he one of the expanding numbers of adults, as well as youth, who are being misdiagnosed with the disorder?

ADHD—Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder—is thought to have a strongly biological basis, with a heritability of around 74%. To that extent the disorder is written into genetics, structured into the brain, and styled in behavior: inattentiveness, distractibility, poor inhibition and impulse control. We tend to think of children, and sometimes adults, whose minds are inclined to drift or whose bodies have difficulty sitting still.

That is not a full description of the diagnosis, nor am I giving clinical advice or questioning the biological assumptions. Don’t stop taking your prescription medication because of anything you read here. Disclaimers aside, it’s worth asking:

Apart from biology, what else influences ADHD symptoms—and attention weaknesses in “ordinary” people?

What story are we telling ourselves about our attention, and is this story helping us?

In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari devotes a chapter to ADHD, where he explores several non-biological factors that can give rise to attention problems. He describes one study that followed the same two hundred people over time, from birth to middle age. Scientists had initially predicted that neurological status at birth—the status of an infant’s brain—would be most likely to predict ADHD.

They were wrong. What mattered most was the child’s social context, especially the amount of chaos and stress in the family environment:

But why would a child growing up in a stressful environment be more likely to have this problem?...When you’re very young, if you get upset or angry, you need an adult to soothe you and calm you down. Over time, as you grow up, if you are soothed enough, you learn to soothe yourself. You internalize the reassurance and relaxation your family gave you. But stressed-out parents, through no fault of their own, find it harder to soothe their children—because they are so amped-up themselves…Their kids are, as a result, more likely to respond to difficult situations by getting angry or distressed—feelings that wreck their focus.

Looking back on my own childhood, I can recall episodes of family conflict that shook me up emotionally, and that had mental ripple effects well beyond the conflict.

But I think it’s fair to suggest the same can happen to adults, no matter what sort of family we grew up in. Stress is preoccupying. It soaks up mental resources, leaving our concentration thinner and less resilient.

It’s the persistent and uncontrolled stress that is most harmful, as it digs into us, burrowing into our weaknesses and sometimes giving rise to entrenched emotional difficulties.

Not surprisingly, some mental health disorders—such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and substance use disorder—often include concentration symptoms, while personality disorders sometimes include impulsivity, which can mimic ADHD impulsivity-hyperactivity.

These disorders can also occur with ADHD, which can make it more difficult to know, for instance, if a person reporting both concentration difficulties and low mood has depression and ADHD, or just depression with concentration issues.

The connection between attention and emotions in mental health disorders is equally true for the treatment of such disorders. Psychotherapy, counselling, mindfulness, even prayerful living—all of these involve the cultivation of attention to the emotions in a gentle and fine-tuned way.

In the case of therapy, for instance, people may initially show up for treatment with vague or simplified perceptions of what’s wrong in their lives—like “everything upsets me” or “I’m always afraid”. It’s as if the inward lens of attention is fogged over, or blurred, so that things are not accurately seen for what they are, but as overwhelming manifestations, like the distorted oversized shadows that are sometimes cast by comparatively small objects.

With care and patience, it’s possible to refine the lens of attention and to see more clearly, although that is only part of the goal. The other part is to be able to separate our inward attention from the distressing thing we’re attending to; to see and feel what is upsetting or frightening us, without getting swept up in it or cowering to avoid it; to become separate from the shadow, rather than being consumed in it.

The goal of improving our inward attention, then, is not to dwell on difficult emotions, but to be more free of them—for we cannot escape what we cannot see.

Not all people need therapy, nor am I suggesting a “therapeutic” lifestyle in which we narcissistically indulge our vulnerabilities. The point is pragmatic: Without mastering an inward kind of attention, one that can quietly observe the flow of one’s inner life, it will be harder for that same attention to turn outward and to observe the world with openness and focus.

Nature exposure

Hari recounts the story of Nicholas Dodman, a vet who concluded that even animals could have ADHD symptoms that are treatable with drugs:

In the mid-1980s he was called as a vet to visit a horse named Poker, who had a problem. Poker was obsessively “cribbing”—a terrible compulsive behavior that around 8% of horses develop when they are shut away in stalls for most of the day. It’s an awkward repetitive action, where the horse will grasp with his teeth onto something solid—like the fence in front of him—then arch his neck, swallow, and grunt hard. He’ll do this again and again, compulsively. The so-called treatments for cribbing at that time were shockingly cruel. Sometimes vets would drill holes into the horse’s face so he couldn’t suck in air, or they would put brass rings in the horse’s lips so he couldn’t grasp the fence. Nicholas was appalled by these practices, and in his search for alternatives, he suddenly had an idea: What if we gave this horse a drug?

In this case, the drug was an injection of naloxone, an opioid blocker, and it worked, at least temporarily. Since then, other drugs have been used to manage the abnormal behavior of penned up animals, such as administering Prozac to a polar bear in a zoo to stop it from pacing endlessly, or giving parrots Xanax and Valium, or antipsychotics to chickens and walruses.

Nicholas Dodman’s conclusion wasn’t that the cause of ADHD or other psychiatric symptoms in animals is purely biological, but rather that, when animals are kept in unnatural, domesticated situations—like a horse spending most of the day in a stall, or a bear living in a zoo—it makes them suffer from “frustrated biological objectives”. In the wild, horses roam free and graze, and polar bears range and hunt in the Arctic.

The same observation can be applied to human beings. Our attention difficulties are not only biological, but stem from our modern, containerized way of living, where most of our time is spend indoors, and increasingly in front of screens, away from the natural environment. The result is what Richard Louv has called Nature-Deficit Disorder—which is not an actual diagnosis, but aptly expresses the basic idea.

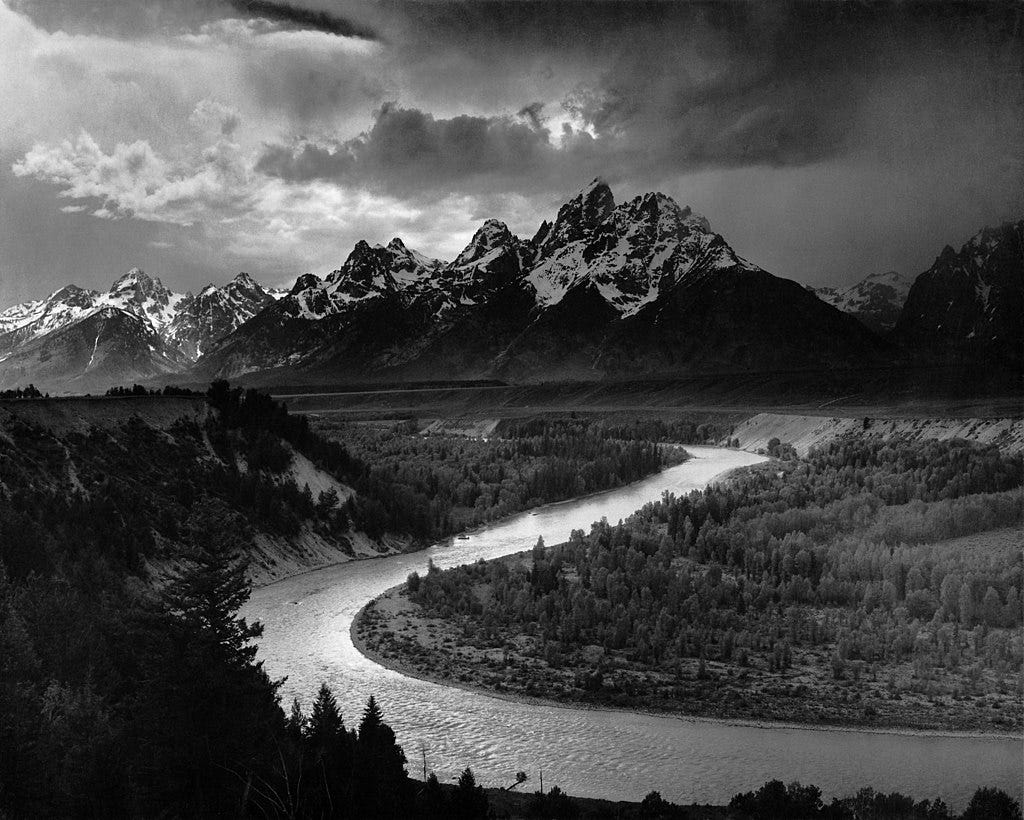

Louv relates the story of one child, from the back page of an October issue of San Francisco magazine, which displays

a vivid photograph of a small boy, eyes wide with excitement and joy, leaping and running on a great expanse of California beach, storm clouds and towering waves behind him. A short article explains that the boy was hyperactive, he had been kicked out of his school, and his parents had not known what to do with him—but they had observed how nature engaged and soothed him. So for years they took their son to beaches, forests, dunes, and rivers to let nature do its work.

The photograph was taken in 1907. The boy was Ansel Adams.

If we are creatures of nature, then nature is salutary to the mind. One theory suggests that nature exposure is good for attention by reducing stress and promoting a more positively-toned state of emotion. If you feel good, your mind is clear.

Another theory suggests that our modern technological lifestyle wears down the mind, and that nature promotes a gentler kind of attention that is mentally restorative.

This gentler attention is known as “soft fascination”, and is often contrasted with “directed attention”. When we direct our attention to a task with a more intense focus, the effort can be fatiguing, wearing down our concentration like an overworked muscle. It has been suggested that “attention fatigue” and ADHD can mirror each other. But soft fascination, which can arise in nature, works differently.

Soft fascination doesn’t require as much effort as directed attention. It is less forceful and less voluntary. If you have ever focused intensively for a long period—say, spending most of the day with eyes glued to a laptop screen—and then gone out to walk in a forest or along a quiet beach, you might experience soft fascination: attention is no longer fixed on a narrow task, or scattered and fragmented by distraction, but rather hovers gently, widely, alert yet calm, noticing much but not clinging to anything. These experiences are relaxing and can restore our mental powers.

The evidence for attention restoration theory is mixed, yet there are enough studies to suggest that the attention and mind benefit from exposure to nature. For instance:

- Exposure to green space has been associated with lower depression, anxiety, aggression, stress and cortisol levels, a lower body and mass index, and higher physical activity and self-reported health status.

- The relationship between greenspace and mental health in children differs depending on age. At younger ages (7 y), higher exposure to greenspace has been associated with lower externalizing behaviors (problem behaviors directed at others), whereas nature exposure among older children (12 y) has been associated with lower internalizing behaviors (problem behaviors directed at themselves).

- In college-aged students, spending as little as 10–20 minutes and up to 50 minutes of sitting or walking in natural settings has been shown to have positive impacts both psychologically and physiologically .

Attention restoration and stress reduction aren’t the only ways nature can help our minds. One of the impacts of nature deficits identified by Louv is the reduction in sensory experiences—of seeing, hearing, smelling, sensing the things of nature—and of the longer-term benefits of these experiences. For instance, a recent study found that children with lower levels of nature exposure grew up to exhibit a greater tendency to miss subtle sensory information, which was, in turn, associated with lower levels of creativity.

Being in nature may not only restore our attention but attune it to certain nuances of perception. We see not only a tree, but rough furrowed bark and low horizontal branches and variably-lobed leaves shiny on top and pale underneath—a bur oak, perhaps. Or we don’t see these details in separation, but the tree as a whole at sunset, standing alone in a farm field, presiding over the hunched silhouettes of wild turkeys.

We sometimes think of our attention as a spotlight, or a smooth surface against which things are perceived, yet our attention has a shape that is profoundly sculpted by experience, filtering some things more clearly than others.

Early each morning I hear birds singing, when the light in the bedroom is still dark, but rarely do I think “robin”, “northern cardinal”, or “wren”, for I am an urbanite mostly, and far more discerning of the sounds of civilization. Sadly, I feel a greater familiarity and even affinity for the Microsoft error-jingle when my wife, who wakens before I do, hits a wrong key on the laptop downstairs.

Hadden Turner has observed that the decline of many bird and other wildlife species in England impacts not only ecological diversity, but our perceptual awareness of this diversity: “We have lost the eyes to see the landscape and know its species by name.”

This “knowing by name” reminds us that nature’s impact goes beyond attention, nourishing our vocabulary and memory as well—the very mental structures that help form our identity. From this perspective, we can see the limitations of thinking of nature exposure in terms of restoration or stress recovery. These terms imply nature is a therapy or treatment for a problem: all we need is the right dose of greenspace, like a medication, and whatever has been damaged can “recover” or be “restored”.

Similarly, the idea of nature exposure turns nature into a kind of mental tanning salon, where we drop in for passive, pleasant mind-beams of soft fascination, before we squirrel ourselves away again into a box-like room where we gaze into a box-shaped screen for eight hours a day, interacting with digital representations of reality.

Nature exposure is not wrong as a Band-Aid-type strategy to be used, as needed—a long walk in a wooded park after a grueling workday might be just the thing to restore a benumbed mind. But if we only go so far, viewing nature as mostly a treatment modality or commodity that gives us relaxation, then the larger context around the problem—the stress and mental fatigue of urban modernity—and the attention-scattering impact of our increasingly device-based existence—doesn’t change.

Attention problems are on the rise

There are other things, beyond emotions and stress and contact with nature, that can impact our attention. I haven’t said anything, for instance, about the potential benefits of physical exercise and certain skilled physical activities in reducing ADHD-type symptoms, or the potential harms of environmental toxins such as lead, phthalates, and bisphenol A, or the impact of excessive device use, among other factors.

The fact that such factors influence ADHD should not be taken as alternative explanations for ADHD as a biological disorder, but rather as things that influence how ADHD and attention difficulties show up in adults and children.

Still, the distinction between ADHD as a biological disorder and ordinary attentional problems in everyday life is not entirely clearcut.

In fact, it is possible that ADHD is not a rigid category, but instead rests on a continuum of severity. So, on the one extreme is severe ADHD—the kind most likely to benefit from medication. Beside that are moderate and milder forms of ADHD, and then there are people who don’t have ADHD, yet do have a vulnerability to being a bit more distractible—and at the opposite extreme are people whose attention is basically okay, yet, under the right situation, can experience disruption in their ability to focus.

The idea that ADHD falls on a continuum of severity might be one (of several) explanations for the rise in ADHD diagnoses in recent years. Doctors may be decreasing their thresholds on the perceived continuum for what they consider to be ADHD, and thus diagnosing people with the condition even though they don’t fit the strict criteria.

According to the standard diagnostic criteria used by psychiatrists and psychologists, ADHD cannot be diagnosed in the absence of any symptoms prior to age 12. So, if somebody goes through childhood with no definite evidence of at least several inattentive or hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, they cannot suddenly acquire ADHD later in life. That does not mean people cannot have serious attentional difficulties later in life, only that the formal diagnosis does not apply.

Despite that, psychiatrists are reporting a rise in people claiming to have ADHD, some of which may be due to a contagion of bad information flowing through social media. As noted by one doctor: “A lot of my patients would hold up their phone to the camera and be like, ‘Here’s this video that I saw on TikTok and this is why I have ADHD’”.

While doctors with ADHD expertise will tend to rule out false diagnoses, some people will still end up misdiagnosed and provided with medication they don’t need or support that isn’t warranted.

In a Canadian study, a report about a fictitious student was sent to 23 colleges and universities, claiming that the student had ADHD. Even though the data in the application indicated the student was in the normal range on every objective measure, 100% of the colleges and universities still approved the application, and agreed to provide the student with accommodations, such as extra time on testing.

This finding is troubling in its own right, as it suggests students without ADHD can get resources that should be reserved for people who truly struggle with the disorder. The same may be said for individuals who, without clear evidence of the disorder, are being inappropriately prescribed ADHD stimulant medications, particularly Ritalin and Adderall.

And it isn’t only people with attentional problems who are seeking medication. It’s also those with normal attention who want to optimize their ability to concentrate. Back to Johann Hari:

I have plenty of adult friends who use stimulants when they have to blitz a work project, and it has the same effect on them. In Los Angeles in 2019, I caught up with my friend…who is a British writer on various TV shows there, and she told me she uses prescribed stimulants when she wants to do a big writing job because they help her to concentrate.

As I mentioned, the criteria for ADHD are fairly strict; only about 7.2 percent of children and 2.5 percent of adults meet the threshold. Why, then, are diagnoses rising, and why are we increasingly willing to provide medication or accommodation when it isn’t warranted?

Attention difficulties are not a new thing, but neither is the sense that we have become a more distractible society. With this, perhaps, we are seeing a shift in our self-perception: it’s as if we expect our attention to be vulnerable. We are becoming more open to seeing normal weaknesses in pathological terms. We are telling a new story about our attention, and our minds as a whole.

The story tends to be highly subjective, which makes it all the more resistant to contrary evidence. The last thing we want anybody to tell us is: “The objective data don’t support your claim to have ADHD. You need to look for other causes. Perhaps you need to address problems in your relationships, or how you live, or manage stress—or maybe you need to tough it out and recognize that doing hard things requires the sustained application of your mental powers.”

To say such a thing, we feel, would be pushing people too hard, even hurting them or disadvantaging them. I should emphasize that I am not referring to children or adults with true, diagnosed attentional difficulties (due to ADHD, or perhaps other disorders); rather, I am referring to an emerging narrative in which ordinary or commonplace attentional weaknesses—like a writer who wants to concentrate better on a big job—are framed as requiring an intervention.

Ironically, the use of technological solutions to address our weakened attention creates a new problem, as it renders us more dependent a narrow range of artificial solutions, whether through medication or perhaps (one day) non-invasive brain stimulating devices. In seeing such solutions as acceptable for “normal” individuals, we weaken the self-sufficiency of our own minds, and we stop looking to address the non-brain causes for our attentional concerns—like difficulties in our emotions, connection with nature, sedentary lifestyles, environmental toxins, among others.

The trend, then, is toward normalizing our attentional weaknesses, and even pathologizing the normal, while offering technological solutions that, by focusing only on the mind, pull us away from the emotional, social, and natural habitats of attention. Our minds are further weakened as a result, progressively more isolated and dependent on artificial methods to function optimally.

In the long run, this trend and the story behind it is a formula for shrinking rather than enlarging what it means to be a person. It erodes the basic structures of human identity, and could make us more susceptible to political and corporate influence and control.

Which suggests a need to be careful about the stories we tell ourselves about our attention. Repeated enough, the stories might come true.

It’s more lucrative to prescribe drugs rather than to prescribe daily walks in the woods... follow the money... Thank you for a lovely essay!

Wonderful essay. I loved this paragraph: "Being in nature may not only restore our attention but attune it to certain nuances of perception. We see not only a tree, but rough furrowed bark and low horizontal branches and variably-lobed leaves shiny on top and pale underneath—a bur oak, perhaps. Or we don’t see these details in separation, but the tree as a whole at sunset, standing alone in a farm field, presiding over the hunched silhouettes of wild turkeys."