Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer. - Maria Rainer Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

I had this globe when I was a kid, and I’d spin it around and close my eyes and wait, then put my finger down and open my eyes to see where I’d landed—Alaska, the Canary Islands, or smack in the middle of the Pacific. I still have this globe somewhere in the house. It’s now old and there’s a chunk missing in the ice of the south pole, so that it’s wobbly on its axis when you spin it around. And that’s one way to describe our own world, I think.

Things are changing, tectonic plates are shifting under our ideological feet, and we feel the instability in our bones. And it isn’t just ideology. As older values and ways of living are increasingly questioned or dismantled, screens and machines are coming to the rescue, and for the most part we are welcoming it.

Just look at how close we’ve gotten to our phones, and lately to AI, and soon, perhaps, to Apple Vision Pro. Our conditioning is almost complete. Most of us have a device-shaped hole in our heart: we don’t quite feel complete without a piece of machine attached to us.

We used to say Jesus filled the hole in our hearts. When we took Communion we were eating the Savior, but now technology, the new savior, does the opposite—it consumes us, dominating more and more of what we do and how we think of ourselves.

“It’s all for the best,” we are told, or something along those lines.

But I sense a shadowy undercurrent, like an unsolved question in my heart, which unnerves me, though I’m trying to be patient with it.

It isn’t in my heart only. It’s the unsolved question of Western civilization.

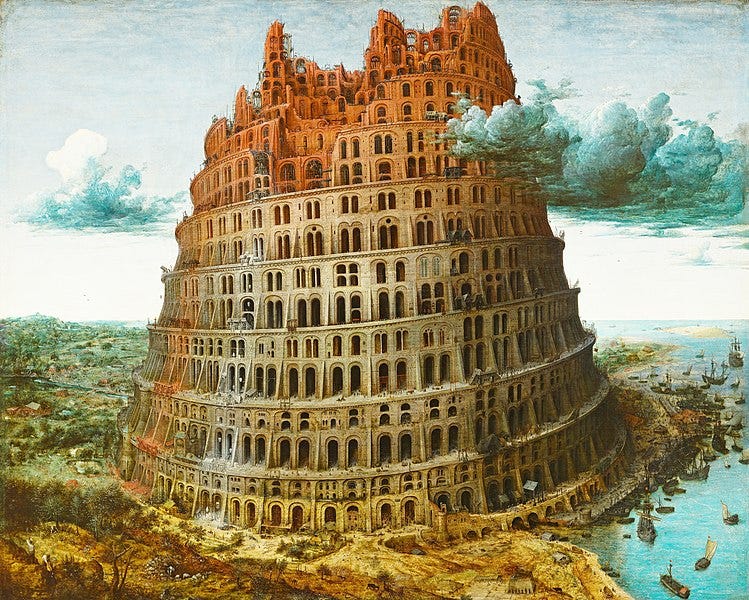

That question stands before us; the locked room of the future has yet to be flung open to reveal what we are making. But something is under construction behind that dark door, something discernible—you need only put your ear to it to hear the sounds and voices. Enough to catch an intimation of what might be coming.

The airport as a Technopolis

There is a tangible aspect of the Machine that I will call “the Technopolis”. It can be compared to a busy international airport—say, Gatwick airport near London. I don’t want to pick on Gatwick, but it stands out in my mind, because I spent many hours inside it while returning from a trip to Switzerland, and many of these very words, in fact, were written while sitting in the dazzlingly dreary north terminal, or maybe the south—I can’t recall—with luggage and family members huddled or dozing on either side of me, and my coffee precariously balanced on a free edge.

An airport’s purpose is to help people find a flying vehicle that will transport them hundreds, or thousands, of miles to new locations. In that sense airports are fingers pointing to different spots on the earth, though unlike my childhood journeys, which never took me beyond my fingertip on a globe, airports are fingers pointing to realities: real journeys, real places.

This miracle exacts a cost. We must leave the little patch of earth we call home, and abandon all things familiar, except for whatever can be stuffed in a box smaller than a grocery cart. Then we journey, perhaps by cab, perhaps through heavy traffic, to the airport building, where we present our ID. Here, in the airport, we are all unique human beings and must be formally identified as such—this particular name, this date of birth, this country of origin—and yet, simultaneously, we are clumped together, as if we’re all the same, as if we are all actually nobody. Then we are shuffled along efficiently with our plastic box, through check-in and through customs, and through a fragrance swamp of duty-free stores, until we emerge in a massive hall of more shops and food courts and a pharmacy and a barren play area for kids with a dirty carpet that would horrify most parents, if they weren’t so resigned and weary.

And swirling through all of this, in eddies and currents, is a crowd of people, perfect strangers from all over the world. In their faces you see every mood, from cheerful to exhausted to hurried. There are people eating BLT sandwiches and getting drunk or laughing, and many are on devices, even myself, and there are bookstores with neatly arranged displays, smelling of fresh ink, recommending narratives of love or horror, or how to succeed in life without giving a f*ck, or how a certain celebrity overcame addiction.

Everything is expensive, yet you are made to feel like a king: it’s all here for you, for your happiness. At the same time, being barely able to afford anything, and toting about your plastic box on wheels, you have almost nothing. In this way the airport foreshadows the WEF promise that you will own nothing and be happy—except, in the airport, you are not really happy, you are more like high, or hyper-stimulated, or tired, or slightly nauseated.

The airport is a Machine Pride event, showcasing not sexuality, but hinting at our future technological city, our hoped-for civilization, promising its many miracles—safety, efficiency, ID systems, fantastic journeys, explorations, endless enticements—laid out in prototype for all to see. Here is a sketch of the Technopolis that might one day overtake urban Western civilization.

And if you can judge a civilization by its toilets, the place reeks.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pilgrims in the Machine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.