The Event Horizon: Lessons from Anatomy and Hiking Shoes

In search of ideas we can live by

Those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen can download the post in an easily printable pdf file. Remember to come back and share your thoughts and comments! You can access the file here:

‘Beware of first-hand ideas!’ exclaimed one of the most advanced of them. ‘First-hand ideas do not really exist. They are but the physical impressions produced by love and fear, and on this gross foundation who could erect a philosophy? Let your ideas be second-hand, and if possible tenth-hand, for then they will be far removed from that disturbing element—direct observation.

– from The Machine Stops by E.M. Forster

Many years ago in Zurich my wife and I stood in a line, shuffling through dim rooms where pools of light glowed against sketches of grotesque faces. Another time, and in another place, we wandered through an exhibit of strange flying machines and mechanical contraptions, and in another time and place, we stood behind a crowd of people who were struggling to observe a woman with an enigmatic smile. The painting of the Mona Lisa was smaller than I had expected, and the tourists, politely squeezing between each other, were almost as fascinating as the painting.

We can learn many things from the genius of Leonardo da Vinci. One of these has nothing to do with art, although it’s more relevant than ever.

In the European 1400s, traditional ideas ruled much of human understanding. Leonardo, who was one of the luminaries of that age, produced drawings of the human anatomy which are celebrated for their accuracy. We take anatomy for granted now, but it was hard to study at the time, partly due to difficulties getting access to corpses for dissection. Leonardo gave close attention to these corpses; to their weird and unsettling veins, muscles, kidneys, and skulls that are ordinarily hidden under a drapery of smooth human skin. As revealed in his written notes, Leonardo knew that dissection wasn’t for everybody, as some artists might be “deterred by the fear of living in the night hours in the company of those corpses, quartered and flayed and horrible to see.”

But Leonardo wasn’t always so attentive to detail. Martin Clayton, the head of Prints and Drawings at Windsor Castle’s Royal Collection Trust, points out that “many of Leonardo’s early anatomical observations were…based on a blend of received wisdom, animal dissection, and mere speculation.”

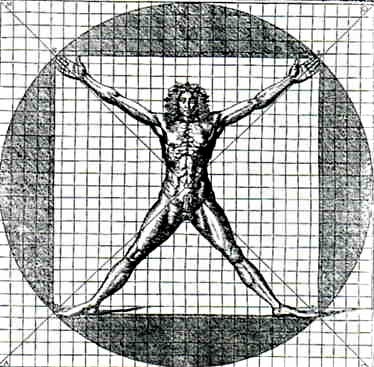

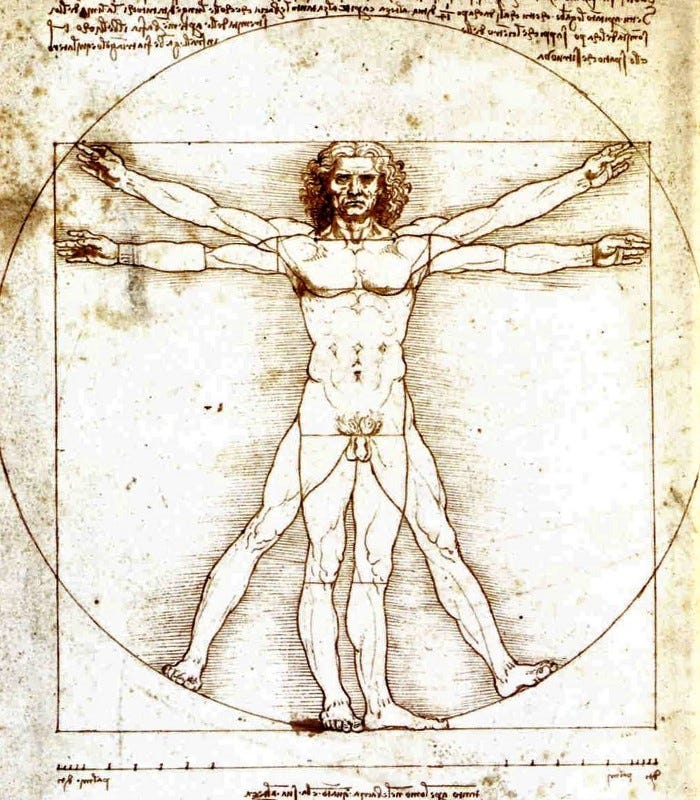

Consider the Vitruvian Man. The drawing was inspired by the first century Roman architect Vitruvius, who described how the human figure, with arms and legs outstretched, could fit perfectly inside a circle and a square. The description involved some simplification in the measurements, so that if slavishly followed by an illustrator, could result in distortion. Here’s a rendering by another artist, Cesare Cesariano, from 1521:

In order to be literally faithful to Vitruvius’s description, Cesariano had to enlarge the hands and stretch out the feet of the figure—all this against a background of gridlines that look like the bars of a cage. The artist has forced geometry and symmetry onto the drawing, yet it’s a distorted symmetry, faithful to his interpretation of Vitruvius yet unfaithful to life.

Leonardo also produced a drawing based on Vitruvius’s description, yet without distortion. However, in order to make things work, Leonardo found it necessary to decouple the circle and the square, and to create two postures from a single figure.

Along with Leonardo’s scrupulous attention to the body, there might have been something else that made his departure from tradition possible: he may have had a reading disability. Leonardo described himself as omo sanze lettere or “an unlettered man” and couldn’t read Latin or Greek—the language through which traditional knowledge was communicated at the time. There is even evidence he was dyslexic and perhaps even had ADHD.

We normally think of these things as limitations, yet these limitations may have helped to liberate Leonardo. While his peers were obsessed with studying the ancient texts of the Latins and Greeks, and idealizing old but not always accurate knowledge, Leonardo was more free to see the world as it was.

Sometimes weakness is strength. Vulnerability can open our eyes.

The event horizon

In Leonardo’s time, the veneration of ancient Greeks and Roman texts produced a mental block in many artists and thinkers. The result was distortion, as in the case of Cesariano’s Vitruvian Man, whose hands and feet were stretched in order to fit an idea, rather than to fit an idea to the man.

Greek and Roman writings don’t occupy the same status in our own time, yet we have our mental blocks. Some of them are ideological. A lot of them flow from our screens. Either way, we can get fixated on certain ideas about life, which in turn can become mental blocks to seeing how things actually are.

Whenever I visit the Alps, I find myself looking up at the snowy peaks and ridgelines, with a longing to know what is on the other side. Of course there are probably just more mountains and valleys on the other side, yet the instinct to climb up there, and to see for myself, never fades.

That same soft fascination can take hold when we gaze down a road that winds into the distance. What is it that we’re looking for on the other side of that horizon, where the landscape tilts beyond our sight? Some new experience? Some surprise?

In space, a black hole has an “event horizon”, which is the point at which nothing, not even light, can escape the pull of its gravity. There are similar horizons in ordinary life, edgelands of new experience that can pull us out of our habitual orbits with irresistible gravity, and plunge us into areas that we never knew existed.

Some of these are small event horizons and might seem trivial, like breaking away from our screen to go outside and wander through the neighborhood or the park. Yet even such little excursions can recalibrate our experience of life. A reliable finding within our own family is that bad moods, which can fester when too much time is spent indoors, suddenly evaporate outside, blowing away like mist; or that children who react with contempt to a suggestion made by their parents will often accept the same suggestion, with surprising enthusiasm, when it comes from an adult outside the family.

In either case—a change in situation or person—part of what’s helpful is the shift in context. Our minds work by association, and changes in context can dislodge old associations and the conditioned habits that accompany them. Crossing an event horizon, even a small one, brings a liberating context shift. When we cross these small thresholds frequently enough, we are filtered with experiences of raw life, while at the same time sifting out a little of the mental dross.

Then there are the big event horizons. Like having children. There are the common challenges, of course, like the toddler tantrums and the adolescent drama, among an infinite variety of circumstances that can contort a parent into every emotion from annoyance to heartbreak. More than all that, though, having a child can pull you across an event horizon that changes you forever.

One of the biggest discoveries on the other side of that horizon, for me, was that I wasn’t half as wonderful as I thought I was. It was humbling to see myself, especially my weaknesses and vulnerabilities and dark side, in a painfully brighter light. I grasped the truth of myself in ways that weren’t possible when I was childless.

But life also acquired a startling freshness. When our kids were small, we made a deliberate decision not to see them as burdens, or as special projects that would last a certain number of years, but as natural enlargements of our lives. We took them almost everywhere we went. We have draped our infants across the tables of restaurants, where they gazed up at the ceiling and wiggled around amid bowls of miso soup and salmon sushi. We have carried them in backpacks and front packs up corkscrew stairways in cathedral towers and down into crypts, and through galleries to see Monet and Rodin. When they were really small, of course, our kids had no idea where they were, and were more fascinated by bits of glittery trash than great art. It didn’t matter. We took them anyway, and as a consequence we experienced something unexpected: we saw the world for the first time again.

Jesus said that unless we become like little children we will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Becoming parents can also make us children, both in the sense of humbling us, and in the sense of reawakening our senses and perceptions.

There are other big event horizons in life, of course, apart from having children, but their effect is similar: crossing that line, and falling into the gravity of raw life, tends to shrink our egos and smash our false assumptions while enlarging our apprehension of things.

One of the byproducts of a machine society is that we’re often surrounded by screens and devices, which can block up the event horizons, leaving us more isolated from each other, and from the outside world, and more exposed to ideas that have been curated by marketers, influencers, and ideologues. But it goes further than that. We actually start to like it.

Now, I’m not saying that people are thinking, I want to live in distortions and fantasies. It’s not that overt. It’s subtler than that. We just get so comfortable that we become willing to sacrifice our event horizons for ease and convenience.

In E.M. Forster’s short story The Machine Stops, the people of the future live alone in comfortable little rooms underground, and in each room is a screen to communicate with the outside world, and everything else the person needs to survive. And they like it. These people also exhibit a strange characteristic, similar to those in Leonardo’s age who idealized the thinking of the ancient Greeks and Romans: they cling to their ideas too much. In fact, the people in Forster’s story want to stay so far away from direct contact with life that they prefer ideas—or ideas about ideas about ideas about ideas:

‘Beware of first-hand ideas!’ exclaimed one of the most advanced of them. ‘First-hand ideas do not really exist. They are but the physical impressions produced by love and fear, and on this gross foundation who could erect a philosophy? Let your ideas be second-hand, and if possible tenth-hand, for then they will be far removed from that disturbing element—direct observation.

Leonardo would have laughed at this, and cried “Direct observation is exactly what we need!” And maybe some of us are laughing too, and thinking that Forster’s depiction is over the top. Who could imagine a society where people not only avoid direct observation, but want their ideas to be recycled again and again, until they are so far removed from direct observation that we can’t even be sure if they’re true?

Some of our machines are designed to recycle ideas in precisely this way. We call them AI models. Artificial intelligence does not have senses as human beings do. What it does do is take our direct observations, and the words and ideas we have expressed about these observations, and it processes and re-processes them and then gives them back to us like regurgitated digital cud.

And we, like the Cesarianos of the Renaissance, or the characters from Forster’s novel, find ourselves comfortable in this sort of world.

Wearing our ideas like hiking shoes

One solution is to swing toward the other extreme, to live by experiences alone, as if we can forever lose our minds and come to our senses, without any great ideas or ideals. But the strange animal called “human” has always inhabited a double-dimension, and we can see it in Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man:

The figure of the man is realistic, almost photographic, which is part of what makes it compelling. But there are abstractions everywhere: his artificial posture, the circle, the square, the bisecting lines, the overall symmetry. Leonardo’s masterful drawing isn’t pure realism, but the marriage of the ideal and the real.

There’s something else too in this marriage: the union is not a union of equals, but a particular kind of marriage in which the ideal is subservient to the real. Despite the deeply conceptual nature of Vitruvian Man, it’s muscularly alive rather than just dryly “symbolizing” something. We, ourselves, are like this too: there are abstract patterns and symmetries in our bodies and in our lives, but we are far more than abstraction.

We don’t need to get rid of all our machines or traditional ideas, yet to avoid distortion they must remain subservient to the realities they are derived from. Achieving this balance of subservience is difficult, as it can mean questioning our own firmly held ideas about the world. We all like to think of ourselves as open-minded, or at least not close-minded, but holding up our most cherished ideas for close inspection can bring on enormous inner resistance. Nobody wants to be wrong.

Now, I’m not going to suggest the postmodern solution, which is now the favored ideal of so many people in the West—to deny objectivity and all certainties as a means of liberating ourselves. I’m going to suggest rather the opposite. Keep your ideas; no, don’t just keep them, but wear them like pants, shirts, socks. Wear them like hiking shoes, and then walk out into the world.

Wear your ideas everywhere you go. Wear them when you clamber up the steep slopes of daily life, and when you wade across the rivers, and when you walk through mud and thornbushes. The ideas you wear may be political beliefs. They may be religious beliefs. They may be social or personal beliefs. Whatever they are, they can’t be tested unless we give them conscious attention every time we step out the door, to see how they stand up against raw, unprocessed experiences of the world: our senses and our perceptions, and those occasional insights or revelations that can turn everything upside down, or sideways.

Wearing our ideas doesn’t mean advertising them to others or trying to prove them in debates. It doesn’t mean waving ideas like flags. It means observing the world around us, and then, over time, seeing whether our assumptions hold up. This requires vulnerability, and relaxing the natural defensiveness we tend to keep around our ideas. Not everybody can do it. Some people’s ideas about life are like a house of cards: they fear to touch or adjust even a single card, for fear the entire structure might collapse.

When Leonardo went into the morgue, he carried some false ideas about the human body based on tradition and speculation—ideas which were shattered by the sight of dissected corpses. Sometimes we have to go into unsettling landscapes, and cross fearful event horizons. The dumb, terrible, no-good ideas will get worn out and tattered, because, if we’re honest, we’ll see that they’re incongruous with life. The decent ideas may be damaged, but can still be repaired with patches and alterations. They can be revised. And the good ideas will endure like good shoes, or like armor. You can wear them anywhere. They’ll hold up. That doesn’t mean they’re exactly true in every tiny detail, but it does mean they’re close enough, durable enough, to tread through the complicated landscapes of life.

We need good ideas to live by, especially in a digital world where bad ideas fester and flourish. We’ve seen this festering in the intellectual anarchy that governs much of the internet, where bad ideas are taken seriously and disseminated merely because there are digital platforms where they can be spread. We’ve seen this festering in fanaticism, where bad ideas are viewed as true by virtue of their constant repetition and familiarity (possibly due to overactivation of the left brain hemisphere, which is heavily involved in both representation and feelings of certainty, as described by Iain McGilchrist). We’ve seen this festering in ideological barbarism, which crushes human beings into concepts and categories. Rather than seeing the human as Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, with proportion and beauty, the result is something like Cesariano’s version—a man forced into a grid in a strained posture, as if stretched across a torture rack, being deformed and broken.

The deforming and breaking that can happen in our ideas about human beings can lead to the deforming and breaking of actual human beings. There are whole societies that live in a Cesariano nightmare. From this we might assume that bad ideas make us suffer, which is often true. But good ideas can make us suffer too.

Fascism and communism have proven bad ideas historically, while democracy has proven a better idea, yet many have suffered and died for both. Suffering is not a reliable indicator of the badness or goodness of an idea. To use suffering in this way might even attract us to the bad ideas that feel good in the short run, like cheap shoes that are soft and comfy when you wear them in the store, but which start falling apart after a few weeks of daily use. Life is filled with piles of ruined shoes that were sold to us by smooth-talking salespeople.

The real test is light. Leonardo went into a dark room to see fearful things, but he went with open eyes and beheld the anatomy of the human being more clearly. C.S. Lewis, speaking from a religious perspective, once wrote, “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.” The same principle can be applied not just in religion, but to all of life.

Do the ideas we wear glow, and reveal things that were previously unseen? Or do the ideas hide, obscure, minimize, cancel, block, blot out, misguide, delude, darken?

Human experiences are complex, and will always challenge our ability to reduce them to tidy concepts. Still, as creatures who inhabit a double-dimension—the world itself, and our ideas about the world—we cannot elude concepts. But like Leonardo, we can keep them subservient to truth.

And if we fail, there is always another event horizon, large or small, another line in the distance where the known world tilts out of sight. That’s where we need to go, beyond the bad ideas, beyond the dead ideas, and across the edgeland, which isn’t really the boundary of a black hole, but of an unknown light.

It’s another chance to see directly again. Another chance to discover an idea we can live by.

Share your comments below!

Links, summer reading, and a long walk

Listen to a free audio version of E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops at LibriVox.

C.S. Lewis’s famous quote “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen…” comes from his essay Is Theology as Poetry? which you can listen to here.

If you want to learn about education the Renaissance way, check out Scot Newstok’s How to Think like Shakespeare, Lessons from a Renaissance Education. It’s a deceptively light and jaunty read, written in short chapters, yet makes for a deep meditation on how we can learn better. It also glimmers with quotable quotes, like:

The root of attention means to stretch toward something. It’s both a physical and a mental effort—one yearns to become one with the object, the slender tendrils of the mind curling around it. We attend to it, just as a servant must attend to a ruler—with all the docility and contortion that implies.

“Who we are depends on who is watching us.” Looking for summer fiction? Check out my novel Exogenesis—imagine Blade Runner meets The Benedict Option—which you can find at online bookstores or at the publisher Ignatius Press. Reviews here.

Join me, my wife Ruth Gaskovski, and Seth Haines on a pilgrimage in Spain next year in June 2025. Space is limited and starting to fill!

I'm beyond taking my socks off to count the people I know who would give me bewildering concerned looks if I broached your topics with them. Some would put the kettle on, some would dial 999.

Not new to say you see the world again through children's eyes but the Sistine Chapel wouldn't be a starting point and the Vitruvian Man would evoke sniggers and pointing not for his proportions but that which hangs forward where his legs meet.

At which stage in life does such thinking begin? I remember a Private Eye cartoon Hom Sap explaining the curvature of the Earth by pointing to a ship on the horizon getting smaller and disappearing. The explainee has a thought bubble with a ship dropping off a precipice to its doom. The Flat Earth exists, a finite extent where speculation and imagination cease, like algebra or petrol to a caveman.

I'm pleased I've read this. Exists there a forum somewhere where ideas can be exchanged face to face?. That you should assemble your ideas on a lonely substack, a fertile ground but somehow barren is a little strange.

I find it interesting that you specifically mentioned hiking shoes rather than just general clothing because I believe the world of shoes is facing problems which mirror the ideas in this article.

Many shoes are designed for their appearance and based on people's preconceived notion of what a shoe is. They are optimized to provide support as if the human body is a rotting building in danger of collapse, and hard protection as if we were bulldozers smashing blindly through everything in our path.

There is a contrary movement which encourages people to go barefoot where possible, and if not then to wear "barefoot shoes". Such shoes are designed to match the form and function of the foot and to allow the feet to be better used as a tactile sense organ, while still providing a basic level of environmental protection. For example the pairs of barefoot shoes I wear daily for both urban and hiking activities are very flexible, have a relatively thin sole, no extra support, and are a bit wider at the ends to accommodate my toes without squishing them.

Barefoot shoes are perhaps the shoe version of Leonardo's Vitruvian Man.