The Phantom and Mr. Jobs: Is there a way to stop brain drain?

Vampire cognition, cue shifts, and salted minds

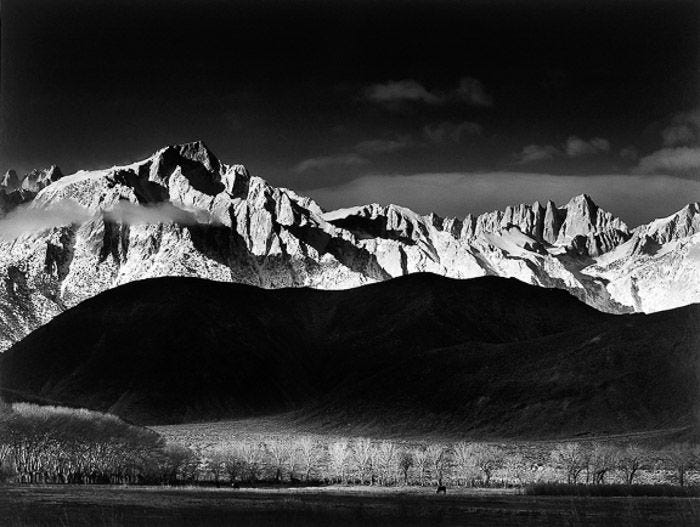

Ansel Adams once waited a week in front of a mountain to take a photograph in Alaska. Then,

“At about 1:30 A.M. the top of the mountain turned pink. Then gradually, the entire sky became golden and the mountain received more sunlight.” After he clicked the shutter, he tried two more photographs, “but within thirty minutes clouds had gathered and obscured the summit, and they soon enveloped the entire mountain.”

I’m not a photographer, but I would love to experience that kind of focus and intensity in my own life. I’m slightly embarrassed to admit it, but my own mountain—the one I sit in front of most days—is a 24-inch computer monitor. Last year, I spent over a thousand hours at work in front of that monitor. This year won’t be much different. The majority of those hours I’m alone, though sometimes I catch the faint creaking of floorboards as my wife or children pass in the hallway, or maybe the jubilant squawking of one of our chickens laying an egg in the backyard coop. And sometimes there’s another presence—a kind of phantom.

I felt it again recently, and it triggered a memory.

A middle-aged man in blue jeans, a black turtleneck, and white sneakers walks onto a stage. Smiling quietly and speaking confidently, he could be mistaken for one of those hip, contemporary preachers—and in a way he is:

Today we’re introducing three revolutionary products…The first one is a widescreen iPod with touch controls. The second is a revolutionary mobile phone. And the third is a breakthrough internet communications device. So, three things…Are you getting it? These are not three separate devices. This is one device!

Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone eighteen years ago, and it’s easy to forget that before Apple’s all-in-one device came on the scene, things were quite different. Back in the old days I had a flip phone for phone calls, a Sony digital camera for pictures, and a laptop for the internet. Three separate technologies for three separate activities.

That wasn’t very efficient, but there was an advantage in keeping them apart, and an unfortunate—yet foreseeable—consequence to squeezing them into a single little box.

The mind works by association. If your mother wears a skin cream with a distinctive scent, you may start to associate it with her and her alone—so that, if you happen to catch a whiff of that cream somewhere else, you think of your mother. The scent was a cue for memory.

Or maybe you’re in love with somebody who happens to wear a purple coat with a yellow scarf, and then, while on a crowded street one day, you spot a flash of purple and yellow and become instantly overwhelmed with longing—only to realize, with utter disappointment, it’s a total stranger. The colors and clothes were cues for an emotion.

Cues can be anything—sights, sounds, smells, objects, locations—that have an association with something in our mind.

Long ago I used to write on a typewriter. I did not take pictures with the typewriter. I did not make phone calls on the typewriter. I only wrote on it. Which means that the sight of the typewriter, pressing on its keys, and the sharp clacking of letters stamping through the ink ribbon, were associated with the act of writing and nothing else.

There was something pure in that experience. A solitude, a depth of focus. When one object (a typewriter) is associated with one mental activity (writing), then the object is less likely to cloud our mind with irrelevant associations, and the more we can focus on what we’re actually doing.

My typewriter is long gone, and here I am, sitting before a computer, transcribing handwritten notes for this essay. My computer, like the iPhone, is an all-in-one device. I use this same computer for communicating, news, videos, work, banking, research—and writing. It’s all very efficient, yet the frequent multitasking can make me more distractible as I water-spider across the surface of different activities, back and forth, back and forth.

A lot of us know that feeling, yet there’s even more going on under the surface.

Vampire cognition

If we habitually do multiple things on a single device, then that device becomes a mental cue associated with all those things. So, even if we’re doing just one thing on our device, our mind remains aware of all the other things we do on that device.

In fact, this is true even if we’re not using the device at all, and it’s just sitting there in our presence.

The laptop is folded shut on the coffee table, or the phone is turned face down. But at some level our mind is still “thinking” about checking our messages or maybe watching a video clip, or else is trying not to think about these things.

There’s a phantom digital presence within us.

The apps on our screens may be idle, but that doesn’t mean they’re idle in our heads. They can silently tug at us without our realizing it, draining a small but precious portion of our mental energy. They are like vampire electricity—like too many electronics plugged into a power bar, sucking away a small percentage of energy even when the electronics are actually idle. We may not notice that we suffer from a case of “vampire cognition” any more than we notice we’re spending a few extra hundred bucks a year due to actual vampire electricity.

Vampire cognition has also been described as “brain drain”, with studies suggesting that

the mere presence of one’s own smartphone may occupy limited-capacity cognitive resources, thereby leaving fewer resources available for other tasks and undercutting cognitive performance.

The most negative impacts are on memory and working memory, and to a lesser extent on attention and general cognitive performance. Some people may be more susceptible to brain drain than others, partly depending on the intensity of their device use.

Minimizing Brain Drain

The most straightforward way to reduce brain drain is to radically reduce our device use, especially during activities that require deep attention—which could be anything from praying to photographing mountains in Alaska to having a heart-to-heart conversation with your spouse.

A second strategy is to do different activities on different devices—work on one, entertainment on another—which might help to keep different mental cues separated and less likely to interfere with each other.

A third approach involves becoming more aware of our mental cues, even when we’re off devices.

Today I went walking in the woods with my wife. The snowy path was soft as a cushion, and in some places heavily trampled, with an underlayer of decomposing leaves that seeped through the whiteness in sallow patches. Further along, we saw the mingled tracks of racoons, rabbits, maybe even a fox or coyote, like stitching across the snow. All these were little things, yet they were all new, and each caused a shift in our usual mental cues.

Until now, we had been at home working hard, our machines quietly bloodsucking our mental resources, our moods stagnating around an overly familiar environment, yet now all the cues were being shaken up. Moods lifted. Thoughts soared a bit higher.

Ruth notices that the snow has fallen on the east side of the tree trunks, rather than on the west side as usual. This changes the entire look of the forest. Cue shift.

I usually walk on the right side of Ruth, but now, quite deliberately, I walk on the left. There shouldn’t be any difference, yet I feel it, as if I’m wearing a shoe on the wrong foot—and it’s not a bad feeling. Cue shift.

Cue shifts keep the mind fresh. We need that. Half of our lives is just boring maintenance. Brush your teeth, vacuum, wipe the counter, do thirty minutes on the treadmill. And maintenance does matter. When we fail to maintain the good yet boring things in our lives, we get cavities, dirty floors and counters, we get flabby. But there’s another half of life that’s not about maintenance, but about shifting our cues in wholesome ways that dislodge us from the usual, the regular, the stagnant, the stale.

It's easy enough to shake up the cues that keep us anchored in stale places. Almost any change of activity, person or location will do the trick—as long as our devices aren’t present or close by, since their presence alone can be an impediment.

Of course, it probably won’t help if we try to change our mental cues just by switching activities on the same device—from Netflix to Substack, from Instagram to MS Word. We might think we’re using only one of our umpteen apps at any given moment, yet their very presence, even if idle, may still siphon away a little brain power.

Mixed pipes and salted minds

All-in-one devices might be producing another weird effect on the mind: the cross-bleeding of associations. We can see this in the very first all-in-one screen device, the TV. Almost from the beginning of television, the same box that entertained us also provided us with news. Is it any wonder that our news became a form of entertainment, or that we sometimes take our entertainment as seriously as the news?

We don’t use the same stage for religious worship and burlesque shows; we don’t use the same room for games of ping pong and litigating court cases.

All-in-one devices don’t just drain our background resources but can mix up our mental cues, creating mash-ups that dilute the purity of any given activity. We run our sewage and drinking water through different pipes for a reason. What about our cognitive pipes?

We Tweet and discuss geopolitics on the same device. Work and play alternate on the same screen. It’s convenient. It’s efficient. It’s not all bad. But in a world where we spend much or most of our waking hours on devices—7 to 16 hours a day by recent estimates—our cognitive pipes can get mixed up, leaking into each other, contaminating the quality of our activities.

We’ve long known that the human mind has limited attentional resources and is highly influenced by mental associations, so the problem of brain drain and the related problem of mixed cognitive pipes should have been foreseeable back when Mr. Jobs was pacing that stage with the fervor of a cool preacher. These are not three separate devices. This is one device!

One device, like Sauron’s one ring: It rules them all. Phone, camera, apps. Mind.

Recognizing this problem doesn’t make us Luddites. All-in-one devices can be useful, particularly in activities that require multitasking and efficiency. But for those of us who are writers and artists, deep learners, monks, poets—for those working at something that, for lack of a better term, might be called “sacred”—then going more slowly and less efficiently isn’t a problem. It’s even a virtue, if it preserves and enhances our mental powers.

Jesus said, “You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.”

To be the “salt of the earth” has a particular meaning in the Christian faith, yet there’s a general application here. Salt preserves food and enhances its flavor. By analogy, a salted human life helps preserve and enhance the world. The same can be said of a “salted” mind. But brain drain does the opposite, desalinating the mind, diminishing its resources and clouding the purity of its content.

Brain drain is just one of many potential negative impacts of our devices, whether distraction, addiction, mental health related, or otherwise. Really, all these are each little vampires, each sinking their digital fangs into different networks of our neural circuitry. As more gets packed into our all-in-one devices—AI being the latest phantom—the more careful we might want to be about how, when, where—and at what age—to allow them into our lives.

And if saltiness matters to you, sprinkle it everywhere—shuffle those mental cues and keep them fresh. Read off paper instead of scrolling. Walk on the opposite side as usual. Do sacred activities off screen. Ponder a mountain for a week.

And don’t let one device rule everything. When the boundaries are clear, the view is more beautiful.

Have you experienced brain drain / vampire cognition?

Do you ever use different devices for different activities?

How do you keep your mind “salted”?

Share you thoughts below…

Offers and announcements

If you found today’s essay informative or encouraging or both, why not support my writing through the purchase of my novel of the future, Exogenesis? It’s available from the publisher, Ignatius Press, or at The Unconformed Bookshop and various other booksellers. Reviews here.

Come and join me, my wife Ruth Gaskovski, and Dixie Dillon Lane on the Camino Pilgrimage in Spain from June 14-24. Space is limited, so reserve your spot now. You can read all about it here or download the brochure here.We would love for you to join us in visiting historic sites, sharing meals, building relationships, all while hiking through a naturally and spiritually inspiring landscape.

Twice now my wife and I have gone back to "dumb" phones. Circumstances made that very difficult a few years ago (needed to make money so did door dash), and the difference is staggering. Three devices are less efficient, but efficiency seems to be the great lie of the modern world.

We are inundated with the idea that efficiency equals competence or ability. What we get instead is lives and art turned into conveyer belts churning out the same thing again and again.

It seeps into family life as well. How easy is it to turn away a child's request because you know it will take too long and they will do it in the most roundabout way possible? How many times have you decided to watch a video instead of look at the instructions for a board game? The world of efficiency has robbed us of depth and understanding. I'm with you all the way on this. The fastest (and probably best) way to escape is to remove the vampires from our lives so we can live fully again.

I share deeply the joy of using dedicated equipment for disparate activities.

I work on a company laptop, but read the news and subscribed magazines on my private one.

If I take photos, it is always with a camera. The whole collection of photos on my phone maybe reaches a dozen, maybe not: an address on a banner, a brand of paint in DIY store, a timetable on a bus stop somewhere on vacation.

The books I read are either printed on paper, or, if digital, on a dedicated e-reader (not a Kindle, actually). Another device to charge and maintain? Yes, but the screen is matt and does not glow. And the device serves to read books.

For listening to the music, I choose my full-size stereo amplifier rather than the phone and headphones. Podcasts—yes—they are better on the phone.

I wear a wrist watch, a simple and legible device with analog look. No need to tap on the phone to tell the time.

A pencil and a scrap of paper for a shopping list.

So, what do I have a phone for?

It reminds me to take away recycled garbage on correct days; the schedule is offen irregular.

And, last but not least, from time to time, I talk with people on the phone. I like talking with people on the phone. If you dig deeply enough in the functions of your device, this leagacy feature is still available!