It’s a late summer night, somewhere in a medieval wilderness, and a man makes his way down a wooded slope and into a meadow, where two figures await him. The man is probably nervous. They are all nervous. Who wouldn’t be, when they’re about to commit treason?

As starlight flickers on the surface of a nearby lake, the three figures raise their hands and swear an oath. They will form an alliance and throw off the oppression of the tyrants who rule over them. They will unite and defend each other—and the people they represent. The year is 1291, and Switzerland has just been born.

Okay, it probably didn’t happen quite that way, and it might not have even happened in 1291, but that’s more or less how the legend goes. If you visit the oath-meadow today—it’s called the Rütli, located on the shores of Lake Lucerne—you won’t find much. There’s a Swiss flag, but there are no statues of the three men who swore the oath, no monuments of power and glory. It’s just a big patch of grass. One of the most important locations in the country is also one of the most subdued. Which is a bit like the Swiss.

I’ve visited Switzerland almost every year for over twenty years, and I also recently became a Swiss citizen. My reasons were mostly personal. My wife and children are all Swiss citizens, and it made both emotional and practical sense that I acquire a citizenship. Beyond this, my appreciation for the country has deepened over the years for many reasons, one of the biggest of which is the Swiss emphasis on localism.

Switzerland is divided into 26 regions or “cantons”, each of which is like a tiny nation with its own language or languages (German, French, Italian, or Romansh), plus a great many Swiss-German dialects that can change from valley to valley. The cantons oversee schools, police, and healthcare, among other things, and are divided into 2300 even smaller municipal regions. And while the Swiss have political parties, key issues are determined through public referendums that can block or change laws proposed by the federal government. These referendums, which occur a number of times each year, tend to de-polarize politics, as they encourage voters to focus on specific issues, rather than on political ideologies or cultish devotion to leaders.

The localist emphasis in Switzerland stands in contrast to my experience of Canada. Now don’t get me wrong. I love Canada. I love its easygoing people, and the cold snowy winters. I love its natural beauty and its sprawling open spaces. The quality of life in Canada is also almost as good as in Switzerland, with the nations ranking number two and number one, respectively, in a 2023 study of “best countries” worldwide. So I’m not complaining about Canada. But there is a crucial difference between Canada and Switzerland—and I don’t mean their geographical size.

To understand this difference, we have to go back to 2015, when Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told the New York Times Magazine that Canada was the world’s “first postnational state”. To non-Canadian ears, that might sound like a surprise. Canada, a post-nation? What does that even mean?

By way of explanation, the PM went on to say, “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada...There are shared values – openness, respect, compassion, willingness to work hard, to be there for each other, to search for equality and justice.”

Most Canadians are naturally sympathetic to these values. I am too. As the child of immigrant parents who arrived in Canada with no money and no English, my family benefited from these values, which helped us to thrive in a foreign land. Still, I’m skeptical of the PM touting Canada as a “post-national” state. Can’t a country have a distinct national character, while also being open, respectful, compassionate, just, and so on? Why do we have to abandon the idea of nationhood in order to possess and promote these core Western values?

In fact, the idea that a nation can be held together by these values, without actually being a nation, is an untested hypothesis. We don’t know if it will work in the long run. When ideals are uprooted from locale, from history, from tradition, they cease to be anchored in real lived experiences that have been sifted carefully through time, and, instead, are at risk of becoming highly abstract. They become a free-floating set of values that are easily swayed by the changing moods of a society, and by the whims of the government. For instance, openness is a great ideal, but should we be open to everything? If not, then who decides? The Prime Minister? The people in his party?

Which brings us to the essence of the problem. The question is not whether a country is national versus post-national, but the extent to which its values are determined locally versus centrally. And that, for the moment, is one of the most profound differences between Switzerland and Canada. For hundreds of years, the Swiss have been diligent in trying to protect the languages and traditions across their many local regions, while also striving (cautiously and discerningly) to be open to other cultures and perspectives. And so far it’s worked comparatively well.

Canada, on the other hand, is placing primary emphasis on unity through ideology, hoping that this—an abstract way of thinking shared across a vast landmass—will be enough to create a cohesive society. And it might. But it’s also a gamble to assume that abstract ideas, centrally managed, will be strong enough to glue a population together. The danger is that Canada might become the ultimate managerial state, the equivalent of a giant condominium complex where strangers from all over the world come to rent or buy; where they agree to follow the condo rules, yet aren’t really committed to the place or to each other; and where the real power rests with a tiny number of federal officials who, like lords in Game of Thrones, stand around an ideological map and ponder how to manage the kingdom.

Today is Canada Day, but I’m still in Switzerland at the moment, sitting by a window that looks onto the rural countryside, where a soft rain is falling across wooded green hills. I love Canada, but it can be hard to believe in a nation that has difficulty believing it’s a nation. That doesn’t mean I have any plans to abandon Canada, which has been my home for most of my life, and where my main roots are. But my experiences in Switzerland over the past two decades have shifted my view about what a country is, or should be.

In 2016, soon after our Prime Minister announced that Canada was a post-national state, celebrated figures like Barack Obama and Bono declared “the world needs more Canada”. Yes, we need more openness, compassion, hard work, and justice—who would disagree with that? But maybe we also need more discernment and honest conversation. Maybe we need to say no to some things. If we want to get the balance right, then maybe what the world needs is not more centralized government and more top-down ideology promoted by managerial elites, but more localism. More local referendums on policy issues. More commitment to local regions. More tax dollars to local governments. More power to local people.

The world needs more Switzerland.

Share your thoughts below. In the meantime, here are 10 glimpses of Switzerland from my current visit:

10. The Original Misty Mountains

J.R.R. Tolkien apparently found his inspiration for many of the landscapes of Middle-Earth after hiking in Switzerland in 1911. It’s hard not to wander through places like this without feeling as if an Elf or an Orc might come wandering out of the trees.

9. The Cheese

Fresh mountain cheese prepared in a salt brine, made by a local family who live near the village of Adelboden.

8. The Cows

And here is where the cheese actually begins. Can milk or cheese taste any better than when it comes from cows that graze on alpine wildflowers? (Too bad I have a dairy allergy!)

7. St. Ursus Cathedral

We spent a lot of time wandering in and around this beautiful Catholic cathedral in the town of Solothurn. According to the city’s tourist website, the cathedral is full of Solothurn’s magic number 11:

…three sets of 11 imposing steps lead up to the cathedral; inside, the cathedral has 11 altars; and the tower is 66 m tall (6 x 11) and has 11 bells. The third complete reconstruction of the cathedral took place from 1762 to 1773 according to a design by Gaetano Matteo Pisoni from Ascona – lasting exactly 11 years.

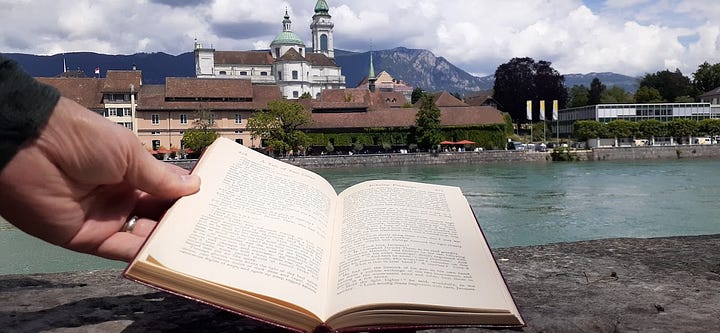

6. A Great Book Find

My wife Ruth found an Everyman’s copy of A Tale of Two Cities in a book box on the Aare River. Nothing brings a reader more delight than to find a great book in an unexpected place. It’s like running into a beloved friend in a strange land.

5. The Sound of Piccolos

The Fasnacht carnival in Basel, dating from the Middle Ages, is a three-day festival that begins on the Monday after Ash Wednesday. Troops of costumed musicians parade through the city, many of them playing tunes on piccolo flutes. Although it’s currently summer and the next Fasnacht is over six months away, you can on occasion hear the musicians practicing. We overheard the clip above while passing an open doorway on a downtown street.

4. Graduation Day

It’s graduation day at a downtown high school—the Gymnasium am Münsterplatz—and the students are celebrating by flinging their school notes out the window while “We Are the Champions” and other classic songs blare over the courtyard.

3. Saharan Sand

One afternoon the sky turned pale orange, and for a while it seemed like it might rain. A few hours later, after the sky had cleared, flecks of dust lay over the entire city. Saharan sand occasionally floats high into the atmosphere, crossing the Mediterranean and the Alps, and settles over Switzerland. You can see the dusting it gave to the snazzy BMW in the photo—not to mention almost every other vehicle in Basel.

2. Swans

Three swans float through a shipyard on the Rhine River.

1. Münster Cathedral

The Münster is the most iconic building in Basel. We sat in on a recent Sunday service, and the pastor announced that the church community would be celebrating its 1000 year anniversary in July. It’s just after 9 pm in the photo above, a few days before the summer solstice, and you can see the rays of the setting sun bringing out the rich red color of the sandstone blocks in the upper half of the building.

2 More Things

Exogenesis

My novel Exogenesis offers a vision of localism versus centralized government in a highly technological future. Author

has called Exogenesis “The best dystopian novel I have ever read. Period.” Find it at the Unconformed Bookshop, most online book sellers, or the publisher, Ignatius Press.A Pilgrimage Out of the Machine

My wife Ruth Gaskovski (from School of the Unconformed) and I will be leading an eleven-day pilgrimage on the Camino trail in Spain next year, from June 14-24, 2025. Joining us, as co-leader, will be writer/photographer Seth Haines fromThe Examine. Space is limited so reserve your spot now. You can read all about it here. This is open to everyone, irrespective of religion or background.

“Post-National” has all the leaning and newspeak of the World Economjc Forum (WEF) and the Davos types who want to re-engineer the world. Switzerland looks and sounds like a great place, my only concern would be their decision to choose a side in the Russian/Ukraine conflict which has damaged their ability to remain neutral. With the bad leadership throughout what remains of the West. I wonder how economically we will fare over the next decade (I’m an American), my thoughts are to go where you can build community (religious and otherwise) self-sufficiency and expect a bumpy ride.

Local is the way forward- agreed.

I have a hard time believing that quality of life survey wherein Canada is #2! Especially when the questions surrounding excess death rates are unanswerable, not to mention the rising popularity of euthanasia.