How Turtles Can Fly

Sometimes the path to originality goes through conventionality

I usually avoid talking to AI the same way I avoid trans fat and telemarketers, but I couldn’t help asking ChatGPT to tell me what makes an “original” scientist, artist, or entrepreneur.

Here was the summary answer, a virtual poem of clichés:

An original scientist, artist, or entrepreneur is someone who:

Sees what others miss,

Dares to break from norms,

Connects seemingly unrelated ideas,

Embraces risk,

And creates from an internal drive rather than imitation.

This answer isn’t just simplistic, but has important shortcomings. I don’t blame AI. AI’s answer is an echo of what many of us already think, a mirror image of our average, stereotypic assumptions about what it takes to be original.

One popular depiction is the wounded genius. Think Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting (a movie I really enjoyed, actually)—you know, the innately brilliant loner who needs only the courage to overcome some inner obstacle, fear, guilt, insecurity, whatever, and once they do, brilliance shines forth, flipping paradigms and breaking barriers.

Now, it’s not that there aren’t people like that—geniuses, non-conformists, iconoclasts, muscled with natural talent, who do see what others miss, do dare to break from norms and soar like eagles.

Yet some originals aren’t eagles. And never will be.

Some are just turtles who manage to fly.

The Housman study

Economist Michael Housman asked a seemingly simple question, and got back a bizarre answer1. The question was,

Why do some customer service agents stay in their jobs longer than others?

He looked at the employment histories of over thirty thousand agents, beginning with the assumption that people with a history of job hopping would be more likely to quit sooner, but instead discovered something totally unexpected. Employees who used Firefox and Chrome were 19% less likely to miss work than people who used Internet Explorer and Safari.

Why would a choice of Internet browser affect people’s likelihood of sticking with a job?

The default browser on most PCs is Internet Explorer. On Apple machines, it is Safari. If you want to use Firefox or Chrome, it means you have to take the extra step to change the old default to the new default. This tiny decision might not seem like much, but it points to something distinctive about that 19% group. They were the kind of people who took initiative. They didn’t accept the default, but tried to think of a better way to do things.

So far, this would seem to align with the idea that original thinkers try to get out of the box and see things differently. Partly, that’s true. But remember, these people were also the ones who were more likely to stick to their jobs, to show up dependably.

So reading the correlation one way, it looks like people who think outside the box are better employees. But if we flip the correlation around, we can interpret it in the opposite direction: people who are more dependable and reliable on the job might be more able to think outside the box.

Herein lies the part of the answer that we tend to overlook. What often makes people original isn’t just their ability to depart from what is normative, but their ability to understand the normative well enough that they know how to depart from it.

And to do that, they need a vital ingredient.

Conscientiousness unpacked

Conscientiousness is one of Big 5 personality factors. As a psychological concept, it includes the elements of competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation. Conscientious people tend to set high standards, and stick to them. They can be slow and careful thinkers, yet they strive to get the job done and well.

And they can be perfectionists, sometimes in the bad sense, and sometimes in the good. Some studies have shown the perfectionism of conscientiousness to be associated with emotional maladjustment, while others have shown it to be associated with positive adjustment and goal achievement.

And there are other advantages to conscientiousness:

Conscientious people live longer, get better grades, commit fewer crimes, earn more (along with their spouses), have greater influence, are more likely to lead companies that succeed long-term, are happier at work, and have better marriages.

They also exercise more, have better diets, and are more likely to engage in preventive medicine.

Plus, they can come with odd quirks: Conscientious people are more likely to believe in free will, possibly as they have a more internalized sense of control; they have a preference for waking up early in the morning; and have a tendency to be more religious.

Which would describe most monks in the world. What if all those generations of tonsured men who lived in chilly, medieval monasteries, dutifully preserving Western culture after the collapse of the Roman empire, were just a personality club of disciplined and detail-oriented guys?

And with the world going the way it is, who knows, we might need another generation of those soon.

Originality through conscientiousness

Still, even with those benefits—better health, better job, longer life, etc.—what does that have to do with creativity? Isn’t actual creativity more associated with being imaginative, sensitive, and curious?

The latter describes another of the Big 5, Openness to Experience, and yes, creative individuals tend to score higher on this factor. So where does conscientiousness fit in?

Actually, it’s easier to start with how it doesn’t. Too much conscientiousness can lead to the unhealthy perfectionism we saw earlier, and can also make us obsessed with detail, rigid, and so narrowminded that it’s not only hard to think outside the box, but hard to imagine there is any other box but the box that we’re already in.

Being a highly conscientious person, I’ve experienced my own pitfalls with this personality trait, as it has helped me to be so efficient, so capable of getting things done, that at times I have suffered the consequences of Braess’ Paradox.

If you haven’t heard of Braess’ Paradox, it’s an observation discovered by German mathematician Dietrich Braess in the study of traffic. In 1990, New York City hosted a massive annual Earth Day event in Central Park. To help accommodate almost a million visitors, a decision was made to shut down 42nd Street, one of the busiest in the city. Many predicted that the shutdown would lead to catastrophic traffic jams on others roads, but strangely, when the day actually arrived, traffic in the surrounding areas didn’t get worse, and even, according to some reports, got better.

Braess’ Paradox could have predicted this. Sometimes, adding roads to a road network can slow down traffic, as individual drivers, motivated by a self-interested desire to get through the network faster, may all begin squeezing into the same shortcut. The result is that the shortcut gets jammed, and the surrounding network also ends up getting slower.

At times, what should be a more efficient solution can paradoxically make things worse.

What is true of traffic may also be true of the mind. In a highly conscientious individual who wants to be creative, hyper-organization can backfire, leading to a preoccupation with getting organized rather than seeing things from a fresh perspective. In my earlier years writing fiction, I experienced this problem when I became so obsessed with plotting stories scene by scene, that the very act of plotting resulted in less spontaneity and surprise in the stories.

A type of Braess’ paradox can sometimes arise when we introduce digital tools into our work. We might use various apps or AI as a means of working more creatively (or effectively), only to find ourselves thwarted by the technology itself—the unexpected notifications, the need to multi-task or task-switch, falling into rabbit holes, and other interruptions that can interfere with what we’re actually trying to get done.

For more conscientious people, the pathway to creativity might mean a deliberate decision to be a little less controlled. If we’re in front of a screen struggling with a creative block, we may want to resist that tenacious urge to stay there, and instead go for a stroll outside, make a coffee, read a passage from a book unrelated to what we’re doing—anything that shuts down our inner 42nd Street and gives our mental Manhattan breathing space.

Sometimes our breakthrough is already there, waiting to emerge, if only we would loosen the reins to allow more spontaneous interstitial time between tasks.

In his book Originals,

observes that a combination of both broad and deep experiences are critical for creativity. The deep experiences, arising from conscientious diligence and hard work, is what gives us expertise in a certain field, whether art, business, or science; but the addition of broad experiences helps us to see things in new ways. As Grant points out, a study of Nobel prize winners revealed that they were much more likely to be involved in the arts than their less accomplished colleagues. The odds of winning a Nobel Prize were twice as great for a scientist who played an instrument, and 22 times as great for one who performed as an amateur actor, dancer, or magician.Pregnant Procrastination

When Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the microphone to deliver his famous “I have a dream” speech, the speech didn’t even include that line yet. He didn’t start writing the speech until after 10 PM the night before, and though he worked on it all night, “not sleeping a week” according to his wife, it still wasn’t entirely ready when he took the podium.

“Great originals are great procrastinators,” Adam Grant observes in Originals. “They procrastinate strategically, making gradual progress by testing and refining different possibilities.”

In this type of procrastination ideas incubate slowly in the pressure cooker of the mind—a pressure that rises as the deadline approaches.

But deadlines aren’t the only pressure cookers of originality.

Michelangelo was miserable painting the 12,000 square foot ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. He didn’t want to do it, he wanted to work on his sculptures, but Pope Julius insisted—and actually sent people out to track him down when he tried to get away.

“My stomach’s squashed under my chin,” Michelangelo wrote in a poem that describes the misery of being hunched on a scaffold with his head craned upwards for more than 12 hours a day.

My beard’s pointing at heaven, my brain’s crushed in a casket, my breast twists like a harpy’s. My brush, above me all the time, dribbles paint so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!…I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.

If Michelangelo hadn’t been under pressure, the Sistine Chapel might never have existed.

But the pressure cooker of creativity isn’t always due to external forces, like an insistent Pope or a deadline.

Sometimes the pressure is internal.

Not long ago, a friend and popular Substacker was at our house for supper. As we chatted over paella in our sunny garden, he happened to mention that on the Big 5, he scored high on both conscientiousness and openness to experience. “It creates an inner tension,” he admitted.

Which makes sense. If you’re highly conscientious, you’re determined to persist with a creative task; but if you’re also open to experience, your mind simultaneously pulls you laterally as it draws in new ideas, some of which might take you off the main task, though other ideas, if you persist, can lead to a more original creation.

Maybe the real anguish of the artist isn’t mental illness as often popularly depicted, but the struggle between the forces of cognitive persistence and cognitive flexibility within the same mind.

Some research supports the idea of dual pathways toward creativity.

Meanwhile, while creativity has usually been associated with openness to experience, both in pop culture and research, newer studies are highlighting the importance of conscientiousness. One study found that people who were high in openness to experience were more creative in their personal lives, but not in their work lives—at work, conscientious people (and extraverts) turned out to be the originals.2

Another study looking at verbal and graphic creativity in students aged 10 to 12, found that openness did predict creativity, but conscientiousness predicted it even better.

“The greater danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark. ” – Michelangelo

Of turtles, beavers and honeybees

Maybe the simplest pathway to creativity through conscientiousness is this: when you know a field really well— whether art, business, engineering, music—then you also understand the totality of it, the whole box, which makes it easier to get out of that box.

Mastering the conventions of a field is the most ordinary path to being original.

“The scientist will be more likely to achieve creative success,” according to creativity researcher Teresa M. Amabile, “if she perseveres through a difficult problem. Indeed, plodding through long dry spells of tedious experimentation increases the probability of truly creative breakthroughs.”

It’s unconventionality, through conventionality.

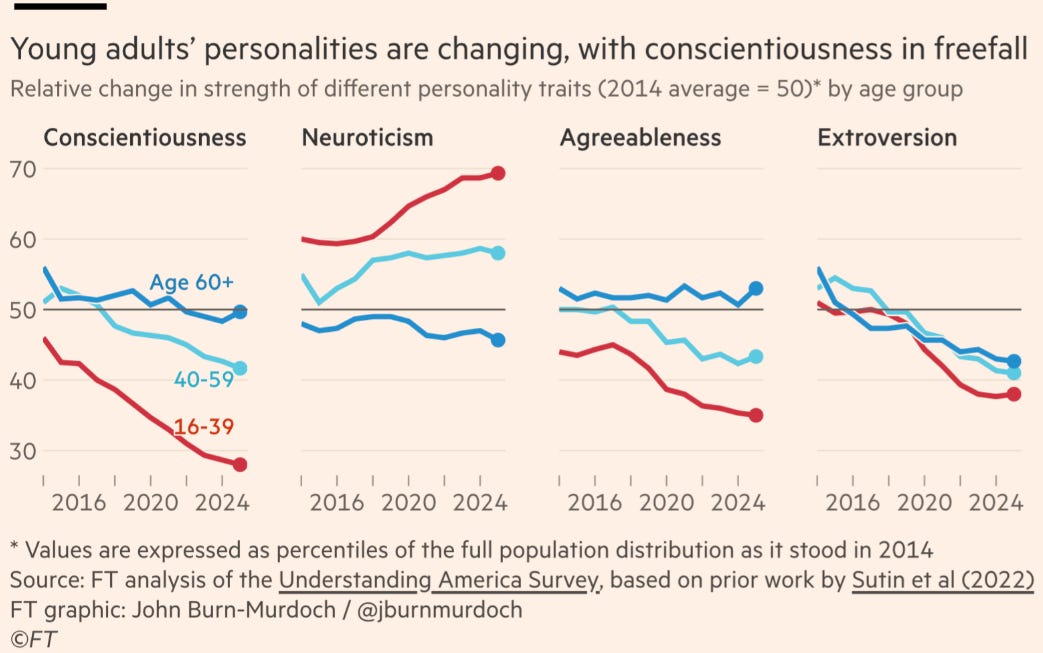

So you’d think that we ought to be encouraging everybody to practice persistence and set high standards. But the latest research, described by John Burn-Murdoch in the Financial Times, suggests conscientiousness is declining, most of all in youth.

Neuroticism (negative emotion) in youth has also risen, while extraversion has broadly declined. All this suggests that many of us, particularly younger people, are less persistent or reliable, emotionally struggling, and less sociable.

According to Burn-Murdoch, the decline in conscientiousness reflects our culture’s excessive emphasis on comfort and instant gratification—and with the rise of artificial intelligence, access to easy answers.

While some have cast doubt on the findings, as Big 5 factors tend to be stable over long time frames, the possibility and the implications are worth pondering.

In the rebellious 60s, the garish 70s, and the New Age 80s, original people were often seen in terms of conventional stereotypes, the rebel, the liberated spirit, the sex, drugs and rock ‘n rollers—and maybe that was to be expected in a world where so many people adhered to a traditional work ethic, put in their 9-to-5, did their duty, didn’t complain.

Now times have changed. Many are no longer embedded in a conventional world where originality is the exception, but in a digital universe where everybody is howling about how original they are, how unique, how great, and we can get caught up in this, not just distracted by it, but satisfied that we too have accomplished something extraordinary by manipulating digital symbols on a glass screen.

Until the dopamine hangover sets in and we find ourselves wondering, Why did I waste my time? What did I really accomplish?

For decades, John Taylor Gatto taught in some of the worst high schools in Manhattan. He should have ended up discouraged by the young people who were his students. Instead he concluded that “genius is as common as dirt”.

But that genius was only possible, he felt, if students were freed from rigid educational conformity and given a chance to develop their unique capacities.

We still need to escape conformity, yet it’s a mistake to define conformity only in terms of rigidity or structure. The new conformity of our age, fueled by digital dependency and increasingly by AI, often encourages emotionality and impulsivity, in effect making it harder for some of us to form stable goals, or to pursue those goals according to a structured plan. The new conformity throws acid on conscientiousness.

What do we do?

The temptation is always to look up at the geniuses, soaring over our heads like eagles, and fantasize about whether there’s a shortcut to becoming one of them.

But we aren’t all eagles. Some of us are slow-thinking turtles, hardworking beavers, dutiful honeybees, stubborn mules, so our path to originality might be along less stereotypic lines.

And there’s a consolation. Even if that originality isn’t recognized or fully realized, conscientiousness still increases the probability that you will earn more, be healthier, and live longer.

Or you might end up a monk, helping save civilization from its excesses.

About the author

As a child in grade school Peco completed his classwork diligently, efficiently, and well. That way he had a lot of time to daydream. He is the author of the novel Exogenesis (Ignatius Press).

This study and a couple of other tidbits in this essay are drawn from Adam Grant’s excellent book Originals, although in some cases my interpretation differs in focus or emphasis.

In more precise statistical terms: “Openness did not show incremental validity in predicting work creativity after controlling for the effects of Extraversion and Conscientiousness, whereas Extraversion and Conscientiousness incrementally contributed to the prediction of work creativity above and beyond Openness.”

As a newlywed, my husband noted that I was not a "go with the flow" type of person (not surprising from an only child who didn't marry until 30). I sat with this observation for a long time, and the image that finally came to me was one of the dutiful animals you name above: the beaver. "She doesn't go with the flow," I told my husband. "She works hard to create a home, and in doing so changes the flow of the river itself." That continues to be a guiding image for my life and work, although I confess that my conscientiousness (always one of my highest traits on all assessments), has suffered over the last few years. Like you, Peco, I also finished my work early in third grade so that I would have time to daydream.That strategy served me well through my 20s, which I spent earning a PhD and taking a post as a literature professor. But with three children (one in a hybrid homeschool), the laundry, the dishes, the suppers, the 'oikosdespoting" (1 Timothy 5:14) no amount of diligence ever yields the time I once treasured to create. There are ways, of course (I write this having risen at 5 to write), but it has been the greatest loneliness I've ever known, trying to create with neither colleagues nor local community to encourage and support.

I'd rather feed the human being with food as energy needed to create than a 20 million square foot AI data center in Utah that will require a gigawatt of power plants to be "creative".

Liked this piece. I use Firefox BTW. Been plodding to get off of the Gates Microsoft and will do so soon..