The Hollow Boys, and Girls: Restoring Risk, Efficacy, and the Small Triumphs of Life

Intrinsic motivation, digital dissipation, and masters and commanders

The tools you guys create actually manufacture unnaturally extreme social needs…It’s like snack food. You know how they engineer this food? They scientifically determine precisely how much salt and fat they need to include to keep you eating. You’re not hungry, you don’t need the food, it does nothing for you, but you keep eating these empty calories. This is what you’re pushing. Same thing. Endless empty calories, but the digital-social equivalent. And you calibrate it so it’s equally addictive…

You know how you finish a bag of chips and you hate yourself? You know you’ve done nothing good for yourself. That’s the same feeling, and you know it is, after some digital binge. You feel wasted and hollow and diminished. - from The Circle, by Dave Eggers

Years ago, long before I (Peco) published my first novel, I lived in a mouse-infested apartment near Toronto’s Little Italy. My roommates sometimes invited me to join them on Friday and Saturday nights, but often I declined, preferring to stay home and write, which was perplexing to them. “Why,” they seemed to wonder, “would you prefer to sit behind a desk, after a week of work and school, when you can come out with friends and drink beer and eat nachos?”

“Why,” I wondered in return, “would I want to waste a whole evening in a sports bar, when I can be here alone, pushing words into intricate patterns to create stories that nobody might ever read? What could be more wonderful than that?”

That was in pre-internet times, when being “alone” didn’t include that nagging background awareness that many of us struggle with today—that we’re never really alone, even when we’re alone, since the WIFI is usually on, a device is usually nearby, and just by touching the screen we can summon a universe of sports bars, nachos, or whatever turns us on.

That nagging awareness can rob us of our intrinsic motivation, though we don’t always notice it. The theft is like mental pickpocketing. We’re already thinking about going online, or we’re already online, by the time we realize what’s been taken from us, though often we don’t realize it at all.

And sometimes we do—like after an online binge. We feed too many electronic Oreos to our brain, and when it’s over we’re “wasted and hollow and diminished”, in Eggers’ words. It’s no accident that our energy levels and sense of substance are bound together. To be energized is to be real.

It can take enormous effort to climb out of the motivational crater that is formed in the wake of a digital binge. Even after we’ve climbed out of it, even after our energy returns, we might notice that our motivation still isn’t the same. The impulses that might catch fire and translate into useful action in the world somehow fail to spark or else lack their usual heat and flare.

“Intrinsic motivation” refers to things we do for their own sake. Not for money or praise, but because they’re inherently satisfying. But harnessing intrinsic motivation can demand a kind of solitude and silence that Machine civilization works hard to disrupt, with all its speed and distracting stimulation. For Gen Z’s, raised in a world of devices, the continual whirl and distraction might not seem strange but the normal state of things, making their challenge even more difficult.

Take a Gen Z youth who spends hours a day on screen. If any delicate sparrows of intrinsic motivation are flitting about his head, he might not notice, or it he does, he might try to pursue them through the screen, as if he could find real things in virtual worlds.

Well, he might, if he’s writing computer code for a software engineering course. But not all intrinsic motivations can be realized within a virtual reality, and probably not even most. We are embodied beings, whose muscles, senses, and mind are intricately tuned to the tangible world.

Still, that might not stop our young man from trying to actualize his humanity online—and it’s hard to blame him. He’s following his instinct, struggling to satisfy his needs for exploration and achievement through virtual adventure, or his needs for intimacy in virtual sex. Even if he senses that something is lacking in these immersive experiences, internet gaming and porn can be addictive, especially to men, and so like pigeons in lab experiments, they will keep pecking for the dopamine kick, hopeless as the effort may be.

Our young man may not even see a need to stop his virtual binging, as society offers him little in the way of a moral or ethical compass for technology. We live in an ethos of digital whateverism: if anyone has a screen, they can do anything, anywhere, anytime. The electronic Oreos are everywhere. So the motivational pickpockets go to work on our young man, stealing away each flicker of intrinsic motivation as it arises in him, slowly bankrupting him of the possibility of discovering what he might actually want out of life.

Even who he might actually be.

A unique struggle for boys

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats' feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion…

from The Hollow Men by T.S. Eliot

According to

, boys, like girls, are suffering from increasing rates of depression, with even higher rates of suicidality. This change has coincided with the advent of social media and devices in the early 2010s. The most striking change for boys, though, is in another variable: a retreat from the real world. Haidt—citing ’ Of Boys and Men—suggests this retreat began in the 1970s, long before the internet. But digital technologies have only complicated that picture:The virtual world was magical for many boys. In addition to letting them interact with new gadgets, it also enabled them to do—safely—the sorts of things they find extremely exciting but not available in real life: for example, jumping out of planes and parachuting into a jungle war zone where they meet up with a few friends to battle other groups of friends to the (virtual) death.

Just as video games became more finely tuned to boys’ greater propensity for coalitional competition, the real world, and especially school, got more frustrating for many boys: Shorter recess, bans on rough and tumble play, and ever more emphasis on sitting still and listening….

And all of this withdrawal happened before the arrival of the metaverse, which is just now taking shape, and before the arrival of increasingly compelling, witty, attractive, and customizable AI girlfriends. The virtual world is becoming ever more immersive and addictive. Every year it will pull harder and harder on boys, urging them to abandon the real world.

If boys are abandoning the real world, then their intrinsic motivation for that world is being abandoned too, and redirected to an often addictive virtual reality. The increased rates of depression and suicide in boys may be a form of motivational rot, the ultimate result of natural energies that have spread into a thousand futile tributaries, like a river diffusing into a swamp. In the old days young men who gave themselves over to sex and alcohol were called “dissipated”. Today we might call it digital dissipation.

The true target of intrinsic motivation is creative efficacy. This kind of efficacy leaves a meaningful or healthy mark on the world. Children stack rocks on a beach, a farmer takes pride in a golden field of wheat, a writer feels pleasure at mastering a sentence. Each stands back and thinks, “I did that.” These rocks and golden stalks and words aren’t just forms of work or leisure. They are little forms of victory, not in the military sense, but as part of a human striving to leave our corner of the universe changed, to imprint ourselves on it, just because we can in our own original way.

And that change goes both ways. When we leave our mark on the real world, we, in turn, are touched, shaped. We are strengthened in who we are and why we are here. This is less likely to happen in virtual reality, where the pixels that make up the “experience” are too unidimensional, too temporary, too distant, to produce either a true mark on the virtual, or a true mark on us.

Someone who works in Silicon Valley might wonder if we could enhance the feeling of efficacy in virtual reality. Higher resolution, brighter colors, better sound, haptic bodysuits that make video games more realistic—for instance when you’re shot or stabbed during a battle. But there is something else about virtual worlds that makes them incapable of fully satisfying our intrinsic motivation: they are too convenient and too safe.

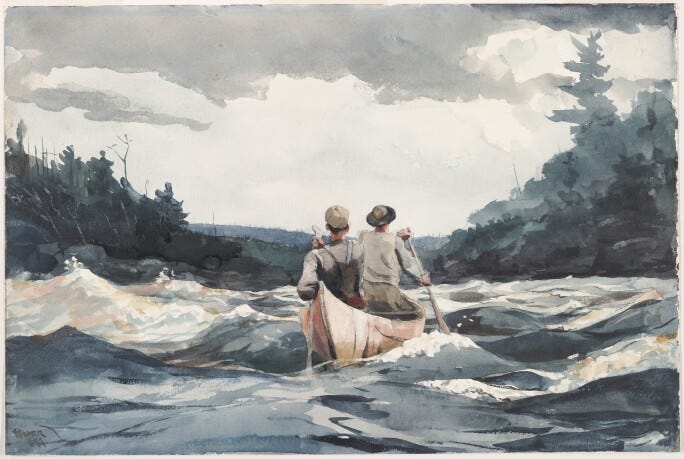

Convenience, safety, and security often figure as major selling points for new tech, yet they are anti-motivational values, even anti-boy. Risk and struggle are vital ingredients in any real adventure1. We need the possibility of actual hurt to actually grow.

describes racing his dirt bike along a woodland trail as an almost spiritual experience when he pushes the ride to the limits of his confidence, sometimes to the point of injury:For a moment, I feel existentially justified. I feel less like a worm, and more like that other thing. The thing I have a constant, nagging sense that I ought to be. In pursuit of this feeling, I once took four trips to the emergency room over the course of twelve months: two broken ribs, a broken heel, what I feared was a separated tendon (it was a muscle strain), and a case of heat stroke…The feeling of exposure one has on a dirt bike recalls one to a basic truth: we are fragile, embodied beings.

Dirt bikes aren’t for everyone, of course. But there are smaller risks we need in life, yet which we seem to be discouraging.

, co-founder of the Let Grow project and author of Free Range Kids, rejects the media message “Your child is in horrible danger”, and instead encourages parents and schools to allow children more independence. Relentless oversight has prompted many children to develop magnified fears of simple activities such as using a knife to chop vegetables (“I could cut myself”), cooking a meal (“I could burn myself”), walking a dog (“the dog could run loose”), or climbing a tree (“I could fall and break an arm”).Not all risk is bodily risk. Mental, emotional, and social challenges can be existentially significant. There are spiritual battles to be fought. There are personal battles as to whether we can keep on loving somebody who might not be easily loved. These experiences, too, can push us beyond the usual limits of our confidence and into realms of anguish and fear.

G.K. Chesterton said that “an adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered”, yet we don’t naturally think this way. We don’t want inconvenience but ease, we don’t want risk but predictability. We don’t want the bruises or tears that will make us grow. And yet, we long for them.

Masters and commanders

Master and Commander2 is film about a British frigate that chases a French privateer through the ocean during the time of the Napoleonic wars. Although released in 2003, the film’s popularity over twenty years later is peculiar, and spawned a GQ article by Gabriella Paiella titled, “Why Are So Many Guys Obsessed With Master and Commander?”

There are almost no female characters in the film, yet Paiella defends its “wholesome” masculinity, as the story is “more about the healthy male bonding between the characters”. She points out that others have similarly described it as “a deeply felt vision of non-toxic masculinity,” and “a portrait of healthy homosociality”.

This is all true, although it’s also an implicitly feminine interpretation, a recognition that men too have natural motivations for close relationships. And of course they do. But this affiliative energy among the characters doesn’t depend only on their relationships, but something existential.

We see men (and boys) struggling to control the sails during fierce storms. We see them battling hand-to-hand against their foes. We see them working together with intense synchronized energy, as if their lives are a continuous competition to prove their strength, courage, and worth. In fact, it’s only when the winds die down, and the ship sits idly in the hot sun for days on end, that the crew begins to crack under the pressure of having nothing to do—as if idleness, rather than war, is the greater threat in life.

If men in the 2020s are still drawn to this film, it’s partly because it speaks to an instinct to face real struggle, real risk—something we can’t get from digital devices or from an overly convenient, overly safe society.

Boys, and girls, may be suffering from higher rates of depression and suicidality, yet for some, what might underlie these symptoms isn’t just a mood disorder, but an inability to be effective in the world, an inability to triumph over their little corner of the universe.

Devices have turned many of our youth into the “hollow” boys and girls of our times. We need to do more than treat their symptoms. We need to help them, and ourselves, see that we can’t live effectively through virtual representations of the world, which only offer, in T.S. Eliot’s words, “paralysed force, gesture without motion”. We need to help them hear the call of their intrinsic motivation, and to fight their good fight in the real world.

Even if it gives them a few bruises, or makes them weep.

The 3Rs: Practical Starting Points

In our essay The 3Rs of Unmachining: Guideposts for an Age of Technological Upheaval, we outlined three essential guideposts - Recognize, Remove, Return - that aim to reorient us toward “embodied reality, face-to-face relationship, and living more fully within our human parameters”. We use this framework here to provide practical starting points for addressing the challenges faced by many boys and girls.

Recognize

The first step is to recognize the impacts of digital technologies and to deepen our awareness and understanding of them. With regard to the issues raised in this post, this may include:

Assessing the level of “nomophobia” - anxiety caused by not having your mobile with you at all times - you can take a test here or here. It is helpful to gain insight into the actual level of dependency.

Making an honest inventory of overall tech use. Most people grossly underestimate how much time they actually spend online. This is a helpful article in Popular Mechanics on assessing your device habits, or you can try Checky.

If you are considering giving your child/young teen access to a smartphone, it is important to consider the content they will inevitably (and at time involuntarily access). I could regale you with horror stories about disturbing online encounters or accessing porn via Spotify. If you want to be horrified and warned, read: So your tween wants a smartphone? Read this first by Michaeleen Doucleff.

For more personal accounts penned by teenagers on the devastating effect of internet porn addiction and gaming, see these entries for The Free Press high school essay contest: I Had a Helicopter Mom. I Found Pornhub Anyway and Why I Traded My Smartphone for an Ax.

If you are concerned about your child’s video game use, Game Quitters is a good place to start. They offer a Video Game Addiction Test (for gamers and parents) as well as Real stories from gaming addicts, which can provide a needed wake-up call.

- reported on a study by Sapien Labs, which found that "the younger the age of getting the first smartphone, the worse the mental health that the young adult reports today".

If you have not yet seen The Social Dilemma, we highly recommend watching this documentary by Tristan Harris, former Google design ethicist who now heads the Center for Humane Technology, together with your kids.

In Charting the Course for Family Tech Use we raised this important reminder: The longer children spend growing up without screens, the more time they have to directly interact with their surroundings, develop an inner self, tolerate boredom and convert it into creativity, and tightly knit their connection to reality.

Remove

In order to begin with restoring real-life engagement, it is necessary to reduce, minimize, or physically remove certain types of technology from our living environment.

For suggestions on creating a “human-friendly” home see:

The Center of Humane Technology offers a long list of “Tips to take control of Tech Use”, including:

Distraction-Free YouTube (Chrome) → Removes those “recommended videos” from the sidebar of YouTube, making you less likely to get sucked into unintentional content-holes.

ScreenSense → Teach healthy tech use to kids, families, and communities.

Freedom (Mac & Windows) → Create custom blocklists on your desktop, tablet and phone for set periods of time.

For support in helping your teen to quit video games, Game Quitters has countless helpful articles, and also offers free support to parents who would like to help their children overcome addictive technology use.

Jonathan Haidt strongly supports a group called Wait until 8th, which “helps parents in each school come together and sign a pledge that they will not give their child a smartphone until 8th grade…so that their children will not be the ‘only one’ who don’t have a smartphone.”

For strategies to talk with your teen about tech use, see A Hostage Negotiator’s Guide to Cognitive Liberty.

For guidance on negotiating tech use in the home for parents, young children, teens, and more on the Postman Pledge, see Charting the Course for Family Tech Use.

Return

The return step goes hand in hand with the remove step; as digital dependence is reduced or minimized, a return to healthy, real-life engagement becomes possible. This in turn strengthens the remove step, allowing the new habits to develop into more permanent life changes.

For children and youth, the Let Grow project founded by Jonathan Haidt, Peter Gray, and Lenore Skenazy, is a helpful starting point to support children in regaining their independence. The project includes practical resources for both parents and teachers, legislative toolkits for “reasonable childhood independence” laws, as well as facts and research about “safety myths”. Commenting on the Let Grow project, Founder

notes,

“Children who have more opportunities than others for independent activities are not only happier in the short run, because the activities engender happiness and a sense of trustworthiness and competence, but also happier in the long run, because independent activities promote the growth of mental capacities for coping effectively with life’s inevitable stressors.”

See also Good News for Anxious Kids (and Parents) by

Below, the ideas and institutions discussed by

and can serve to inspire your own projects and grass-roots groups:- , former Marine Corps platoon commander turned classical educator (as well as journalist and poet), integrates “Beowulf, Teddy Roosevelt, and Tennyson…alongside log drills, land nav, and tourniquets over the course of the unapologetically strenuous camp.” See his articles Low-crawl Leadership as well as Survival Among the Cyborgs on Adam's Curse. See also Illiad Athletics.

- introduces several institutions that recognize the need for integration of manual and mental labor training “entire humans – mind, character, spirit, and body.” These include for example:

St. Andrew’s Academy, which integrates academics and faith with farming and the trades: “These elementary and fundamentally human activities provide nourishment not only for the body, but also the mind and soul because they provide regular experience with reality, experiences that are a prerequisite to reflection and abstract thought...A cultivation of the manual arts develops an integral part of man, informing his understanding of himself and of his place in the world.”

Others discussed include : The Maker Institute, the College of St. Joseph the Worker, Harmel Academy, as well as other non-explicitly religious institutions such as the American College of the Building Arts and the Work Colleges Consortium.

If your child is interested in gaming, why not join the droves of people who have discovered the joy of tabletop games? See Small Plastic Gods: On the Tabletop Renaissance by Steven Knepper:

People are hungry for real-world connection and community. Tabletop games put something in our twitchy, swipe-hungry fingers other than a digital device—a hand of cards, a pair of dice, a plastic Zeus. And since others have put down their phones too, we can look out over those cards into a human face, a present human face.

For additional ideas to reengage with real life see:

Last Child in the Woods - resource guide by Richard Louv.

National Wildlife Federation’s Great American Campout

Further Reading (and Listening)

I’m Worried About the Boys, Too by

- ’s conversation with the author of Boys and Men Richard V. Reeves

Risky Play: Why Children Seek It and Need It by

- interview with Johann Hari, author of Stolen Focus (podcast and transcript).

We imprisoned our children. In fact, the only place where our kids get to feel they’re roaming around at the moment is on Fortnite and on World of Warcraft. We can hardly be surprised that they’ve become so obsessed with them

It’s Time to Dismantle the Technopoly3 by Cal Newport

Just because a tool exists and is popular doesn’t mean that we’re stuck with it. Given the increasing reach and power of recent innovations, adopting this attitude might even have existential ramifications. In a world where a tool like TikTok can, seemingly out of nowhere, suddenly convince untold thousands of users that maybe Osama bin Laden wasn’t so bad, or in which new A.I. models can, in the span of only a year, introduce a distressingly human-like intelligence into the daily lives of millions, we have no other reasonable choice but to reassert autonomy over the role of technology in shaping our shared story. This requires a shift in thinking.

What Are You Sacrificing to the Algorithm? by

Avoid the quick hit, the content churn, the incentives offered by the machines. Slow cook an idea. Create a project with flavor, nuance, and artistic integrity. Go deep and long instead of short and shallow. Make work that matters. Buy work that matters. Support work that matters.

Resist what’s easy. Resist the machine. Resist the algorithm. Resist; resist; resist. In that resistance, find a more human way of being.

Also…

Thanks to all the readers who have responded to our New Year’s questions in relation to devices or any new/emerging technology: 1. What is your problem? 2. What fears do you have? 3. What hopes do you have? We have made note of the concerns and issues raised and will strive to address them in our writing in the coming year. If you would like to add your responses, you can do so here:

We would love to hear from you! Please share your thoughts, reflections, and questions in the comments below.

Until next time,

Peco and Ruth

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), and if you would like to support our work of putting together a book on “The Making of UnMachine Minds”, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share.

UK sun article: Fascinating black-and-white photos (spanning from the 1930s to 1970s) show children playing in the streets and alleyways before technology tempted kids indoors.

"That nagging awareness can rob us of our intrinsic motivation, though we don’t always notice it. The theft is like mental pickpocketing. We’re already thinking about going online, or we’re already online, by the time we realize what’s been taken from us, though often we don’t realize it at all."

This is brilliant. I would also add how this robbing actually also (paradoxically) fills us - it saturates our mind and mental capacity so that we are exhausted for good work/attention. Thus, as well as being hollowed out and diminished, as Eggers says, we are also filled - with junk. (Which limits our capacity to be filled with goodness).

As a mother to four boys I think about this need to put their physical drive to use often. It’s one of the primary reasons we’re evaluating a major life change — so they have space and actual jobs to expend energy. In the city we do our best to find physical outlets for them, and they are active with great imaginations, but to have them feel that their activities contributed to something in a meaningful ideal would be wonderful. Another thought that kept returning to me throughout reading was how vital it is for bodies to be able to move, in order to complete a stress cycle. There’s a natural response of adrenaline and cortisol that happens when we’re stressed — and there’s no end to this being delivered via screen, but without the body actually moving through discharging the adrenaline it just stays locked in the body, making one more reactive and less regulated. All mammals have some way of returning to equilibrium after a threat, but we seem to have discounted the amount of threat we subject ourselves to by just reading the news or playing a video game. I didn’t realize how many jolts of cortisol I got just scrolling Instagram, and the algorithms are finely tuned to get the most response.