When I first read ’s book The Master and His Emissary, I didn’t just learn something profound about the neuropsychology of the human mind, but experienced a transformation in my own perception of life—and I’m hardly the first person to make this observation.

So, against that background, today’s post is a McGilchrist-inspired exploration of how we see the world, through the lens of an ancient icon.

The Orthodox monastery of St. Catherine’s lies at the heart of the Sinai Desert. Built between 548 and 565 A.D., way back in the Emperor Justinian I’s days, the monastery contains the oldest continuously operating library in the world.

It is also home to a 1500-year-old face. To some the face has religious significance, yet it also carries mysteries that tell us something about our own minds.

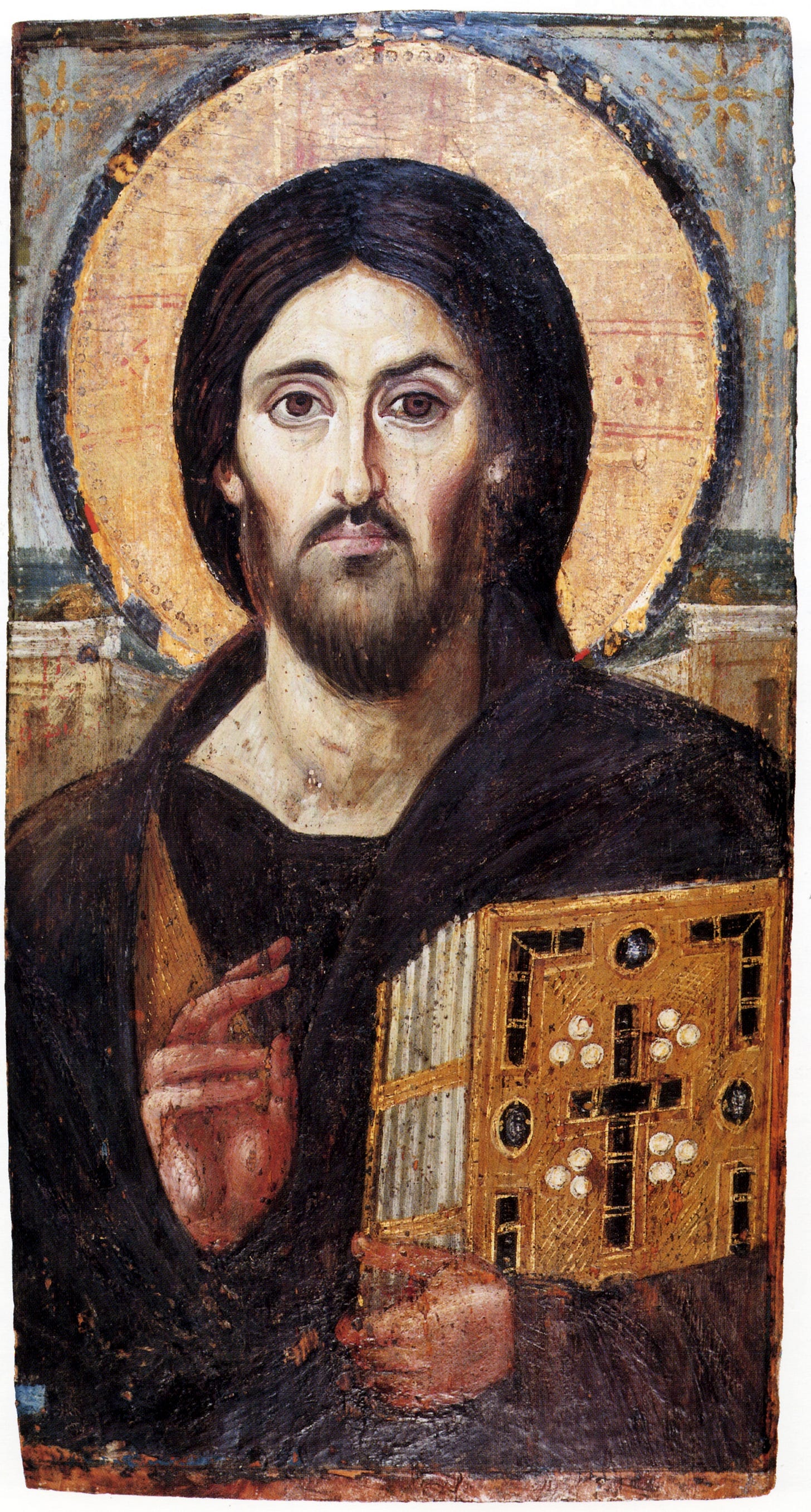

The icon of Christ Pantocrator dates from the 6th century A.D. Painted on a thin wood panel, it’s one of the oldest depictions of Christ, and the oldest image that shows him as “Pantocrator”.

Derived from the Greek, Pantocrator literally means “the ruler of all”, although some have suggested a more accurate translation is “all-holding” or “all-sustaining”.

The icon of the Pantocrator is a descendent of the art of Constantinople, although it’s also a continuation of an earlier tradition of “mummy portraits” from Romanized Egypt.

Now, to the mysteries.

Looking more closely at the Pantocrator, there’s a striking difference between the right and left half of the face. The right half of the face (the left, from our viewpoint), is softer and more luminous. There is less shadowing, and the eye is brighter, the eyebrow more curved, and the eye—if you look right at the pupil—is looking upwards rather than directly at the viewer. The right side of the mouth is relaxed. The overall emotion on the right half of the face is calm, pensive, non-confrontational.

The left half of the face is more shadowed, the cheekbone more prominent, and the mouth is slightly pinched. The eye is darker, the eyebrow more angular, and the eye is looking directly at the viewer. The overall emotional tone of the left half of the icon is stern, distant, judging.

These contrasts are not an accident. They echo a central tenet of Orthodox (and orthodox) Christianity: that Christ is fully human and fully divine. He is like us, and can even suffer and die like us; and yet he is infinitely remote, judging humanity from the vantage of eternity. This mysterious union of human and divine natures is known as “hypostatic union”. It’s an existential asymmetry, and if it seems completely paradoxical, it is. There’s an old saying that goes, “Orthodoxy is paradoxy”.

Yet there’s another asymmetrical mystery in the Pantocrator’s face. The left side of the face is emotionally more intense. This too has significance, not theologically, but neuropsychologically.

The brain has two hemispheres, left and right. Although both hemispheres are involved in emotion, the right hemisphere is more involved in emotion processing1, including the expression of emotion in the face2. And, because the brain is “contralaterally” organized—the right hemisphere tends to control the left half of the human body, and vice versa—the increased emotional intensity shows up on the left side of the Pantrocrator’s face.

There’s another asymmetry to consider, one described by

in his extraordinary book The Master and His Emissary.3According to McGilchrist, our brain perceives the world in two distinct ways: the right hemisphere tends to see things wholistically and experientially, whereas the left hemisphere tends to perceive the world abstractly, in parts and divisions, and in linguistic and representational terms.

The right hemisphere is also more capable of processing ambiguities. It takes things “as they are”, so to speak. It can handle uncertainty, and it’s more empathic, and more in tune with the emotion of sadness. In contrast, the left hemisphere “needs certainty and needs to be right”, according to McGilchrist. And the left hemisphere isn’t just more prone to certainty, it is less empathic and more in tune with the emotion of anger.

So, broadly speaking, the human mind operates through two modes of perception, and we can see elements of these modes suggested in the icon of the Pantrocrator: the brighter side of the face appears more empathic, even tinged with sadness, whereas the more shadowed side of the face appears more certain and angry.

Now, the point here is not about the Pantrocrator’s brain; rather, the point is simply how the face of the icon itself expresses two modes in which our own brains function. The icon doesn’t only theologically express the dual nature of Christ, but conveys something of the dual nature of the human mind.

McGilrchist suggests that, in healthy individuals and societies, the more wholistic mode of perception (right hemisphere) tends to take the lead in how we see the world, while the more representational mode (left hemisphere) tends takes a secondary position. Both modes of perception are needed, and integrated into a single perception in our actual experience, yet ideally the right hemisphere tends to lead (to be more dominant) while the left follows. The one is “master”, the other “emissary”.

When we look at the Pantrocrator, the right hemisphere of our own brain—which is more involved in facial and emotion processing—naturally directs our gaze toward the left side of the icon. We may not notice this consciously4. Yet the overall effect is that, even though we see both halves of the Pantrocrator’s face while looking at it, the right half of his face (the left side, from our perspective), will tend to dominate our overall perception of the face. In effect, the brighter, more open side moderates the more shadowed, sterner side. The human side of Christ softens the divine side of Christ.

I don’t mean to suggest that this tells us how Christ’s duality is balanced within his own nature. But it does tell us something about how the artist inclines us to see that duality. Whether he (or she?) knew it or not, the icon painter is subtly encouraging the viewer to see Christ’s mercy more prominently than his moral judgement. Both mercy and moral judgment matter, and both are suggested in the icon, and yet the shift of emphasis puts them in a particular balance.

The icon might look very differently, if the painter had depicted the duality in reverse, as shown below:

Viewed in reverse, the image takes on an emotionally darker aspect. It’s as if the sterner aspect of the face (now to our left) is too strong, too overwhelming. Again, we cannot precisely know how Christ’s dual-nature is balanced within himself; the mind of God is a mystery. But the way that we depict God is consequential in how we then understand the Divine—and this is not just a theological issue.

The two images below, courtesy of Wikipedia, are distorted versions of the Pantocrator. Each is a composite of one half of the icon’s face. To the left is the face based on only the left side of the face (mirror-imaged). To the right is the face based on only the right side of the face.

Notice how meek and mild the face on the right looks. It is the face of the stereotypic liberal “Jesus”. He is the nice Jesus, capable of compassion and pity, yet incapable of any moral judgment.

The face on the left is all sternness and judgement. It is the face of the stereotypic conservative “Jesus”. This is the Jesus who only sees your sins, and isn’t particularly loving, or maybe just abstractly loving, though you can’t actually feel it. He is too cold to be an empathic god.

Both of these are “false christs”. They are the inventions of human beings, often the highly intellectual or highly political who manipulate religion to reflect either own personality preferences, theories, or social values agendas.

We are all human, of course, and so invariably, we all project something of our own biases onto God. Every concept of absolute Reality will be distorted by the tension in our own dual-nature; mercy versus judgement, intuition versus rationality, heart versus head. At a theological level, the Christian faith is continually distorted by the gravitational pull of our mind; at a human level, our perception of the world is distorted in just the same way.

The visual structure of the Pantocrator icon suggests that if we wish to un-distort our perception of the world, then the way is to lead with mercy, intuition, and heart, and to follow with rationality and the head.

I doubt this was consciously intended by the artist, who was simply trying to depict the mystery of hypostatic union. But that itself conforms to the method of un-distortion: often it’s our least conscious efforts that give rise to our most inspired creations.

Balancing our empathy and judgment, our head and heart, and the other dualities of our nature is an old human struggle. As moderns, we might be cynical about religious approaches to coping with this struggle, or that there are monks, even in our own time, who might spend all day in front of a painted icon. Yet we gladly spend all day in front of that other icon, the smartphone, our hearts and heads given over to machine algorithms that groom self-absorption and manipulate our opinions.

The image of the Pantocrator is powerful, yet the image itself is not an answer to our struggle. It is only a symbol, a window. Its true power is that it directs us away from ourselves and the grasping forces of this world, toward the infinitely Real.

Links and Further Reading

Iain McGilchrist just started his own Substack, and I encourage you to check it out, along with his remarkable books, The Master and His Emissary, and its sequel, The Matter with Things.

Pilgrimage Reminder: Come and join me, Ruth Gaskovski, and Dixie Dillon Lane on the Camino Pilgrimage in Spain from June 14-24. Space is limited, so reserve your spot now. You can read all about it here or download the brochure here. We would love for you to join us in visiting historic sites, sharing meals, building relationships, all while hiking through a naturally and spiritually inspiring landscape.

There are some exceptions and nuances to this generalization.

Particularly the lower two-thirds of the face.

My summary of his ideas here is very simplified!

And again, there can be exceptions to this generalization.

Peco, I am so glad you posted this. Did you know about Iain's deep fascination with and study of the phenomenon you describe here? At his course at Schumacher College over a decade ago, one of the sessions was an impromptu lecture and slide show of many such icons and their left and right composite versions. It was a fascinating talk, especially for someone like me, 'at home' with some aspects of Modern Art but a complete ingenue to icons and religious painting at all (apart from perhaps the Flemish masters...)

Wonderful piece, a window...

The digital library version in 2025

https://sinaimanuscripts.library.ucla.edu