When I clicked on the button, the mysterious icon appeared, floating beside my text. Rewrite with Copilot, it said.

I thought, Rewrite? I didn’t ask Copilot to rewrite. I didn’t even know I had Copilot—which, I now understand, is Microsoft’s AI assistant, ready to leap out of the corners of our screens like digital divas, desperate to sing for us.1

Just a few months ago, AI was being dissed as underwhelming, maybe even dangerous, falling short of its promises, yet now Copilot is nagging me to click, DeepSeek is taking the world by storm (possibly through intellectual theft), the Vatican has issued an official statement2 warning of the risks of AI, and

is saying I told you so!3Like it or not, AI is sizzling, and in a tech-hungry society, where apps and devices are digging into every nook of our lives like famished rats, I have no illusions. AI will keep growing—and yes, there will be some benefits. We don’t need to reject all forms of AI to be critical of AI.

Now is the time to start drawing lines about where we might not want artificial intelligence. We all need to become a little Amish, or rather AImish4, about vital areas of life—and for me, one of those areas is writing.

I’m not talking about any sort of writing. I’m not worried about AI spitting out a manual for how to repair a 2009 Honda Civic, or a newspaper article summarizing tomorrow’s weather. But I am concerned about any kind of writing that comes from the heart—stories, poems, personal reflections, love letters, letters of apology, and (speaking as a novelist) novels.

AI has a tendency to focus on the “center” of the training data, resulting in outputs that are bland and conventional. AI sentences often feel as if they are made not of wood or stone but plastic. And the more we consume it, the more our own words and ideas start to acquire that polyurethane quality.

I can already hear the objection to my objection. But AI is still pretty good and it will only get better over time—so why not give it a try? Why not let AI write a personal essay, or at least do part of the work, like editing the text, if it can do the work faster or better?

This reasoning makes sense in a culture where product matters more than process, where the ends justify the means. If AI can write a better novel, a better personal essay or love letter, then why not? Won’t its positive impact on the world be that much greater?

And many writers, including

, are already recognizing that impact—with trepidation.Impact. There’s a buzz word we love, a word that got made when imp and pact were stapled together in a contract to sell our souls for success. Everyone wants to make an impact on the world, though in the wilderness of social media and pop culture, that often devolves into manipulating others, or just being a narcissist. Look what I did! Well, except that AI did it. But maybe people won’t actually admit that? Or else they’ll put it in the small print. AI is the new steroids, except for writing, not muscles, injected quietly when nobody is watching. If everyone’s doing it, then there’s nothing wrong with taking it—and anyway, how else will I keep up with the competition?

And really, why shouldn’t we—continues the argument—be the best that we can be?

And I am sympathetic to being the best that I can be. I’m an optimizer. A perfectionist. If I do a job, I want it to be not just a good job, but a superb job. I want people to feel like they’re getting something for their time or money.

Okay, then if that’s true, shouldn’t I feel obligated to use AI in my writing, to produce the “best” possible product? Am I not depriving people of the very best I can offer by not using AI?

For the most part, I admit there is no going back. Our society, our leaders, our investors, and most people who use tech, are happy to jump on the AI sled and go careening down the slippery slope. And I’m under no illusions that an obscure essay by a little-known writer is going to make the slightest bit of difference. Still, for those who sense there is a problem, there are a couple of things to consider.

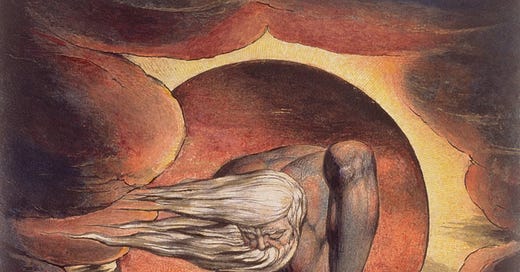

We are not machines. We are embodied creatures who possess something which—for lack of a better word—is a spirit. I’m not even speaking here from a religious perspective. I’m referring to something tangible in our experience. When we tell a story, or try to express our love or feelings to another person, or even just raise our hands to a beautiful night sky and utter a cry of wonder and gratitude, we are not simply using words. What we perceive in the world outside of us reaches into our spirit, and our spirit responds by reaching back into the world. We do not speak merely to communicate, but to participate in a bond.

When we write about matters of the heart, our words ride that bond, going back and forth between spirit and world, world and spirit, like electricity crackling along a wire. When we allow something artificial into that wire, we are interfering with, blocking, distorting that connection.

And it can be very subtle. Increasingly, I notice that when I’m writing directly onto a computer screen, something feels off. I stare at the sentence I’ve written. It looks correct. It seems to say what it needs to say. But no, something is wrong. So I take a piece of paper, and I start writing that same sentence on the paper, and I’ve only gotten through a few words when something mysterious begins to happen. The paper begins to speak to me. No, I don’t hear a voice in my head. But a deeper process seems to take over, and the words emerge in ways I could not have anticipated. When I compare what I’ve written on the page with what I wrote on the screen, the scrawling of my ink is often fuller and truer.

We focus so much on the “impact” that we might have on the outside world, that we can forget about the impact on ourselves, on our interior world. But the heart and the spirit aren’t the only ways that AI editing and writing apps can disrupt us.

I wrote recently about vampire cognition:

The apps on our screens may be idle, but that doesn’t mean they’re idle in our heads. They can silently tug at us without our realizing it, draining a small but precious portion of our mental energy. They are like vampire electricity—like too many electronics plugged into a power bar, sucking away a small percentage of energy even when the electronics are actually idle. We may not notice that we suffer from a case of “vampire cognition” any more than we notice we’re spending a few extra hundred bucks a year due to actual vampire electricity.

AI—even if we’re ignoring it, even if the digital diva is sulking in the corner of the screen—can create a degree of vampire cognition, distracting us from the act of writing. Somewhere in the back of our minds, we’re thinking, Maybe AI can write this better?

I love the Scrabble dictionary. It’s not a proper dictionary with definitions, but just a list of words, hawed, hawfinch, hawfinches, hawing, 500 pages of lists, each an intricate pillar of letters. And each of these words, when I browse through the pages, alights on a thin branch of memory, like a skittish bird, usually flying off again when I turn the page. And so I forget that I ever saw giddap, or subdeb, and querida and foodery—yet I might not, if I turn the words into a sentence.

With a shout of “Giddap!”, the pretty subdeb rode her horse to the foodery to meet her admirer, where she told him bluntly, “I’m not your querida, okay?”

One of the hard realities of human cognition is that most of our major mental functions peak in our 20s, and tend to decline, slowly but inexorably, in the decades that follow. But one of the exceptions is crystallized knowledge, and in particular our vocabulary, which can continue to increase until at least age 60—and maybe into our late 60s and 70s.

Writing that comes from the heart or spirit is inspiration, and that’s one thing we need to protect from AI; but writing is also mental work, effort, 90% perspiration, and we need to protect that part too. We need to flex our writing muscles if we want to keep them, and remarkably, it seems we can keep the vocabulary muscles, and the crystallized knowledge muscles, quite late into life. Mystery writer PD James published her last novel, Death Comes to Pemberley, when she was 91, which should give consolation to anyone who hopes to grow old and still have the power to weave a thoughtful sentence or a whip-smart retort.

There is an old argument about technology, that goes something like this: We’ve always had new technologies, and the world hasn’t come to an end. The same argument, superficially, can be made about writing. A long time ago oral storytellers told stories around a fire. Later, people scratched stories onto tablets and scrolls. Later came books. Then the typewriter. Then the computer. Then dictation software. At no point did people cease to be able to write, so why should we worry about AI? Isn’t it just another advancement?

But there is a critical difference. Previous advancements over thousands of years have never offered to take away most of the mental work, or most of the inspiration, from the task of writing. But AI does. Got writer’s block? No problem, here’s a prompt. Don’t like it? Here’s another prompt. And another. And another. Got an idea, involving a subdeb, a querida, and a foodery? Here’s a sentence for you. Here’s a short story. Here’s a novel. The diva is ready to leap onstage and do the singing.

The Amish drew a line by staying off the electrical grid. Now it’s time for us to decide on our own limits with AI. Where will we draw the AImish line?

When we look back at our technologically less-sophisticated ancestors, we might laugh at them for believing that angels and demons perched on their shoulders, whispering into their ears. But we can stop laughing now. The demons have arrived. They are perched on the edges of our screens, just a half-inch away. Never was temptation so brazen, so brilliant. It remains to be seen whether the angels of our better nature will give us wise counsel—and if they do, whether we’ll take it.

For my part, I’m staying AImish when it comes to writing. I’d rather sing my own song, imperfectly.

Offers and announcements

You can support this writing through the purchase of my novel Exogenesis, available from the publisher, Ignatius Press, or at The Unconformed Bookshop and various other booksellers. Reviews here.

Come and join me, Ruth Gaskovski, and Dixie Dillon Lane on the Camino Pilgrimage in Spain from June 14-24. Space is limited, so reserve your spot now. You can read all about it here or download the brochure here. We would love for you to join us in visiting historic sites, sharing meals, building relationships, all while hiking through a naturally and spiritually inspiring landscape.

Thanks to

for pointing out that Microsoft might have automatically switched many of us to the upgraded (and more expensive) Copilot version of Office 365. He saved me 30 UK pounds. I owe you a beer, or a tea, Hadden!Thanks to

for drawing my attention to this statement. See his commentary When the Vatican Talks About Artificial Intelligence, Pay AttentionAnd

has noted the UK government’s proposed changes regarding AI, involving allowing LLMs to use copyrighted content for training unless people deliberately opt out.